Weakness for the Sake of Strength

Our world is caught in a surreal stasis. A pandemic flows over us, and while its consequences ripple around us daily, many of us are existing in suspended animation.

We’re living in a time when we’re asked to deny ourselves agency – to refrain from exercising control and influence.

We’ve stepped back from daily life as we’ve come to know it. Many of us have pulled our strength, our activities, our productivity, our ability, and in short, our power, inward; we’ve retreated into the interiors of our homes, our immediate families, and ourselves.

We’ve submitted: we’ve suppressed our individual agency, obeying our governments and our scientific and medical experts, precisely in order to conserve that agency – to “flatten the curve,” to save lives, and to hold on, however tentatively, to the preservation of that which we once took, perhaps, too lightly.

What we took for granted – especially in the West where our liberty and affluence have reached a level unparalleled in history – was our ability to move, act, be productive, and engineer benefit and comfort for ourselves and for society in general.

Of course, natural disasters regularly occur in specific regions: a hurricane here; a tornado there; earthquakes, fires, locusts, diseases, famines – even murderous wasps – strike in one place and then another across the globe.

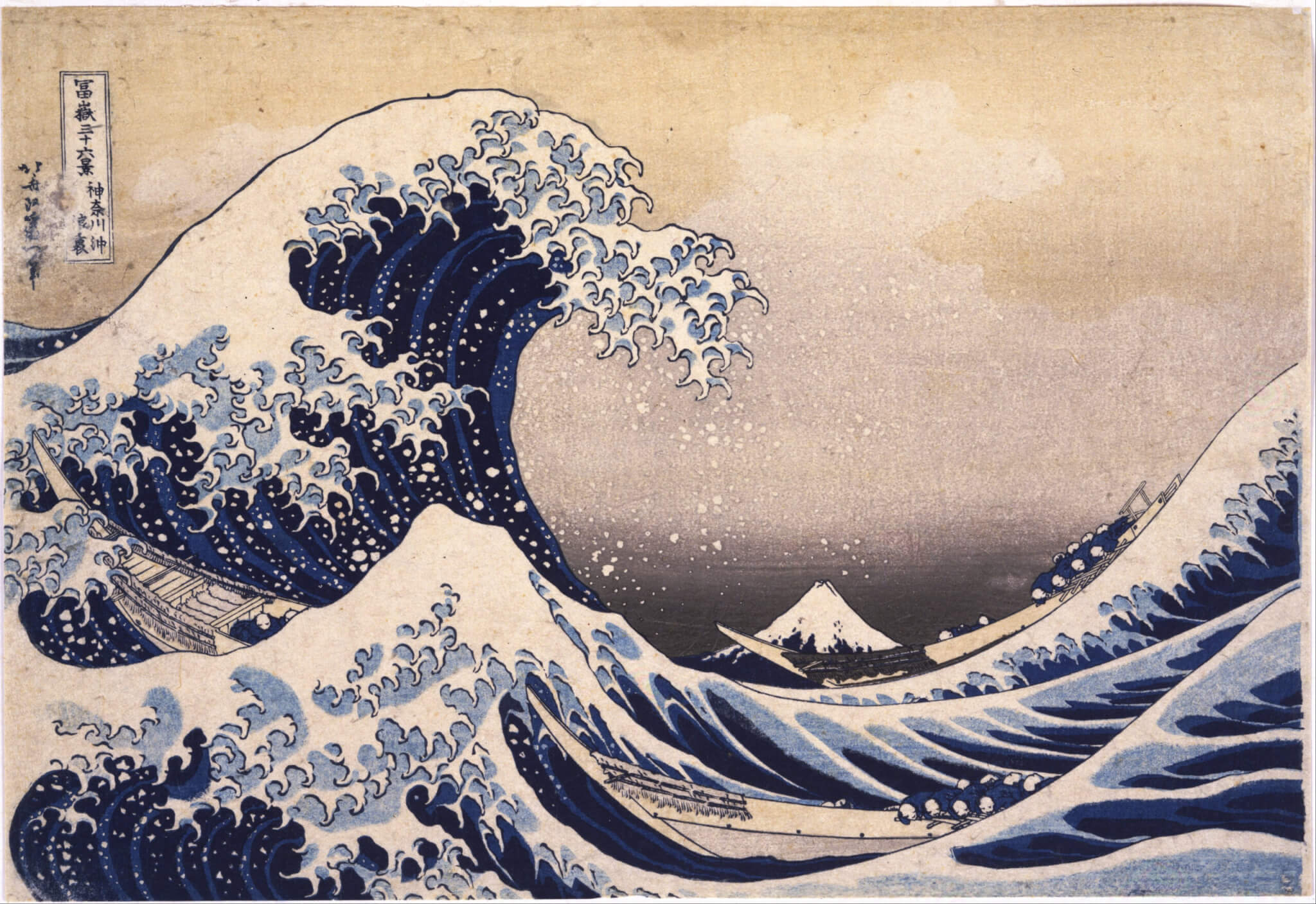

But it’s something new to have a tsunami of disease engulf all the world as we – eyes glued to our screens which endlessly flash images, numbers, and analyses – helplessly watch.

During this time, we’ve intentionally weakened ourselves and denied ourselves agency with the hope that doing so will allow us to once again be strong.

This time in history is gravely momentous to us – if feels extraordinary, unprecedented, and at the very least existentially unsettling if not terrifying.

Yet at the same time, this process of becoming weak in order to be strong, paradoxical as it may seem, is not exceptional. We live in such states of paradox all the time, in familiar and often ordinary ways.

We put ourselves under the care of physicians, submitting to their diagnoses and plans, to be rid of illnesses which hinder our strength; in doing so, we give up some of our own independent, individual agency so doctors may act on our behalf and, we hope, heal us.

This is exemplified the most starkly in the cases of surgery, especially when it involves anesthesia. But even when we are “just” sick, having come down with a common ailment, aren’t we told to rest – to build up the capacity to fully resume our activities?

In similar ways, we submit to those in authority over us, following their rules and directives in order to receive provision and protection from them.

In essence, this is the basis of Locke’s Social Contract, upon which much of our Western ideal of government rests: we agree to give up some of the freedoms we enjoy when we are independent so that we may preserve other freedoms while we live within a secure social order.

Don’t entire armies discipline themselves to submit to military authority, giving up individual agency in order to function as effective martial bodies? Don’t powerful athletes submit to their coaches, trusting that their mentors will channel their strengths into victories? And don’t gifted artists of all kinds regularly place themselves beneath the dictates of their instructors, hoping to successfully hone their creative abilities and skills?

We also find this truth in many processes of life. When a car hydroplanes, we inhibit our agency by not forcing radical movement on the vehicle and causing loss of control. When overcome by a wave, we allow it to buoy us, swimming with it, rather than fighting against it in order to conserve strength. When a woman labors she must not fight it; she must give way to the physical forces which will bring about birth.

Consider that even when we sleep, our energies depleted by the activities of the day, we give up agency in order to cultivate greater strength for challenges of the coming morning. What could possibly be more mundane, more humdrum and everyday, than that?

In these situations, we lean into the challenges of the circumstances. We allow ourselves to be weak in order to become strong.

This process is a fundamental aspect of life as a human being. It’s something we’ve done for millennia, and we continue to do each day, all the time, in various ways.

In fact, it’s a critical element of an important component of our civilization: education. For education to happen, students must voluntarily give up some agency. They must submit to teachers. They must at times be still, they must trust, and they must be attentive. Eventually, they submit to the material – whether it be mathematical formulas, literature tropes, or theological truths – that they’re learning.

Submission, contrary to how we usually think about it (which is often in a less than positive sense), isn’t so much the negation of agency as the intentional, personal suppression of it. Think of it as an act – perhaps even an art – of deference.

Submission is not the same as subjugation. Rather, it is the willing relinquishment of a certain portion of agency, often precisely in order to gain agency back in greater measure.Ideally, after you submit to the doctor and you are healed, you become sturdier; after your coach or instructor has worked upon you, your performance improves; after you have slept, you are stronger.

It’s true that the “ideal” is not always achieved. Sometimes the car spins out of control even when we do our best to avoid it; at other times the wave may carry us farther than we ever intended, perhaps to our detriment; sometimes we go to our rest at night and we don’t wake. We live in a dangerous world.

For the most part, however, this pattern of giving way in order to make our way is a successful means by which we move through our daily lives. We navigate using this pattern all the time.

Submission to another person is allowing in yourself a condition of weakness or vulnerability in order to then receive something which will make you more robust; it is, ironically, taking from another what he or she is willing to offer, such as healing, protection, ability, knowledge, success, and wisdom.

Submission allows us to be receptive to what others can give us. In the case of education, in large measure this entails receptivity to what others, to whom we voluntarily give authority, reveal to us.

Ultimately, authentic authority requires sacrifice – the giving of one’s self to others. That giving away of self means you’re willing to be weakened in order to strengthen someone else. A teacher gives of himself or herself for the sake of the student.

Ultimately, submission to authority requires the willingness to humble oneself in order to be edified, perhaps even exalted – for all good teachers wish for their students to surpass them.

Ultimately, the student submits to the teacher (be it a person, a book, or even an idea…) in order to gain authority which then, in turn, may be used to strengthen others. The student becomes the master.

This dance between teacher and student, a delicate balance of submission and sacrifice, is quintessentially classical and Christian.

It’s classical because Socrates taught it at the dawn of the academy as we know it: he who is wise (in other words, strong) is so because he first acknowledges he is ignorant (in other words, weak). He submits and learns. It’s Christian, for as Paul wrote that the Lord said to him, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness” (2 Corinthians 12:9).

Kate Deddens

Kate Deddens attended International Baccalaureate schools in Iran, India, and East Africa, and received a BA in the Liberal Arts from St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland and a MA in Mental Health therapy from Western Kentucky University. She married her college sweetheart and fellow St. John’s graduate, Ted, and for nearly three decades they have nurtured each other, a family, a home school, and a home-based business. They have four children and have home educated classically for over twenty years. Working as a tutor and facilitator, Kate is active in homeschooling communities and has also worked with Classical Conversations as a director and tutor, in program training and development, and as co-author of several CCMM publications such as the Classical Acts and Facts History cards. Her articles have sporadically appeared at The Imaginative Conservative, The Old Schoolhouse Magazine, Teach Them Diligently, and Classical Conversations Writers Circle.