A Symposium with Aristotle

It is said that one day the Caliph Mamun saw a bald-headed man with a long beard and broad forehead sitting on his private couch. In awe and with a trembling voice the Caliph inquired: “Who are you?” The man replied, “I am Aristotle.”

– 9th century Islamic legend

For most of the evening, I had been reading in my room at a desk built from empty wooden wine crates and a thrift-store-find end table. My old lamp poured light over pens and papers, a wine bottle still three quarters full, and an open copy of the Nicomachean Ethics. I was deep in thought, considering a particular question – an uncomfortable but intriguing question growing in my mind since I’d come across the phrase “the Philosopher will, more than any other, be happy.” Certain modes of concentration cause a loss of connection with time and the senses. I don’t recall how long I was in that suspended state when I was suddenly aware of a strange noise behind me.

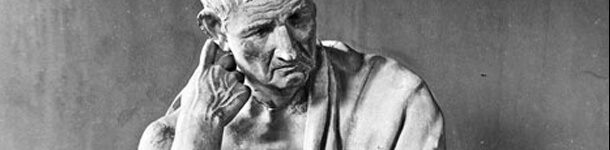

It wasn’t actually strange; it was the quite usual sound of the sigh of springs in my reclining chair, which I hear repeatedly throughout the day. What made the familiar sound so strange – for a moment, ominous – was that I’d been alone in the room a moment before. Dread, curiosity and surprise erupted simultaneously, and startled me back to the present. I reflexively turned to see the cause of the noise. An old man, he wouldn’t have been very tall if standing but he seemed weighty, a broad-shouldered old man with a long beard and sand-colored robes was sitting casually in my chair as if waiting. He stared calmly at me with eyes blue as the Aegean.

“Who…?” I began, but lifting his hand with a dismissive gesture, he brushed away the question.

“I believe you had something to ask me,” he said.

For a moment, I couldn’t even remember what I’d been pondering all evening. I simply stared back at him in mild unbelief. He smiled and said, “Those who know will pass their time more pleasantly than those who inquire. But both may equally enjoy a glass of wine during the lesson.” My brain coming ‘on-line’ (so to speak), I immediately stood up to fetch an extra coffee mug and I poured him some of the Bordeaux I’d opened an hour earlier.

“Very good!” he said, “we’ll make it a proper Symposium, and have your question as the topic of our discussion.” He took a drink of the wine and settled back into the chair. He seemed ready for me to begin.

“Well…Sir?” I fumbled. I didn’t know if Aristotle was a first or last name, and I wanted to be polite. “We were reading your Ethics.” I paused a moment in case he wanted to speak, but his eyes were closed, listening. I took a deep breath. “And I want to know, is it possible to be a Philosopher in a Democracy?” Immediately, I found myself a little embarrassed by the simplicity of the question and I wondered if he would think me arrogant for asking it. I ventured a follow-up: “Do you think this is a good question?”

He opened his eyes. “The problem we have is that your question seems rather vague.”

I’d thought it almost too specific. I asked, “How is it vague?”

“Because,” he said, “you have three terms which are unclear. And, if I may be frank, I don’t mean that your question is unclear generally, though it is. I mean that it is as yet unclear to you.”

I was intrigued. I thought that I’d simplified and considered the question carefully enough. “Which terms?” I asked.

“To begin with, Democracy and Philosopher. Tell me, what is a Democracy?”

“Government by the people” I replied automatically. Too automatically, I realized.

“Is that an answer from either your reading or your experience?” he asked.

“Well…not exactly either one,” I said. I was simultaneously thinking of elementary school stories of Pilgrims, the Pledge of Allegiance, the Cold War, and the phrase ‘inalienable rights.’ I was confused, and wondered if it showed. I said, “Obviously, Democracy as we’ve been reading about it is different from what I’ve been taught before. But, to be honest, I haven’t really considered my experience of Democracy enough to compare it to what I believe about it.” This was an uncomfortable notion. I expected that we would pause to discuss the disconnection between my experience and my education, but Aristotle seemed keen to press on.

“You’ve read two lists of governments in your classes so far. Can you remember them?”

I knew he was referring to Socrates’ list in the Republic and to his own list half-way through the Ethics. “Yes,” I said, “I think I remember both lists.”

“Remind me what they have in common.”

Again, I hesitated. I’d always been taught that Plato and Aristotle were irreconcilable, and therefore any question of what they had in common was novel. I offered the first thing that came to mind. “For both, Democracy was toward the end of a chain of types. A downward chain in both cases.”

“Go on,” he said.

“Monarchy was the first and best in both lists. Tyranny was the worst in both, if I remember. Tyranny looks like Monarchy, but as a mirror image or inversion. Democracy falls somewhere in between. It doesn’t arise spontaneously, and – at least for Socrates – it isn’t stable. It’s a sort of compromise?” I finished, rather lamely. I wasn’t sure what else to say without the next prompt.

“You’ve reached two important points,” he said, nodding. “Democracy is not the best or worst, and it seems to be a transition between other governmental forms.”

This did not sound like progress to me, but Aristotle didn’t seem to mind. He continued, “Do you remember the context of the two lists of government?”

“I think that Socrates was about to – or maybe just did – show how governments were like individual souls. I don’t remember which produced the other exactly, whether Democracy produced democratic souls or democratic souls made Democracy.”

“And what was the context in my Ethics?”

“Your context was friendship. I remember that because it seemed a strange place to have a list of governments. But you said that justice and friendship are connected, and that equality and likeness are forms of friendship.”

“Good,” he said, “so both Socrates and I agree (I caught the hint of a wink at the word ‘agree’) that democracy is neither the best nor the worst form of government and also that government is intimately connected to personal relationships – to the souls of individuals or groups.”

“But you also said that in the ‘deviation forms’ as you called them, friendship and justice hardly exist. So,” I protested, “Democracy is government by the people; wouldn’t justice be more present rather than less?”

“But consider,” he mused, “isn’t any government to which the citizens consent a government ‘by the people?’ And wouldn’t the people choose the best form of government if it was available to them? And if they don’t have a choice, can it be called ‘consent’?”

“Most people are born into a government already established,” I said, “They can’t exactly choose. Or…” Again, I was brought up short. I was, in fact, confused about Democracy. What was it? How did it come about? I had taken for granted that it was the best of possible governments until I read Plato, and here was someone who had lived in the birth-place of Democracy suggesting that it wasn’t what I’d been taught. I thought of Aristotle’s comparison of a Monarchy to a well-ordered family. But he had said that ‘Democracy is found chiefly in masterless dwellings.’ Was America a masterless dwelling? Is it less than good for everyone to have ‘license to do as he pleases?’ I needed to consider this further. I could see how my question – if a Philosopher could live in a Democracy – was unanswerable until I had some better grasp of Democracy.

The old man took another sip of wine. “I can see from your silence that you’ve understood my point about the vagueness of your question,” he said. “We will come back to Democracy, but let’s move on for a moment. The next word we need to consider is Philosopher. What is a Philosopher?”

I couldn’t help but catch the joke in my reply: “I suppose sir, in our society a Philosopher is someone with a degree in philosophy.”

“That’s very telling,” he said, and for the first time I detected the hint of a frown. “But go on. Your question arose while reading Ethics. How does the Ethics describe the true Philosopher?”

I pondered for a moment the irony of recalling for Aristotle his own description of the contemplative man. “There is a lot to say,” I said.

“Sum up for me what made the greatest impression on you.”

“Well, you said that perfection involves will and deed, and that the Philosopher has both to the greatest degree. He is involved in the activity closest to the gods and he is dearest to the gods. The issue you brought up at the beginning of your book – happiness – you tied especially to the Philosopher. You said that ‘happiness is a form of contemplation’, so it seems that everyone has a little of the Philosopher inside or some kind of potential or attraction to Philosophy. I was just thinking about this when you…dropped in.”

“Yes,” Aristotle said, leaning forward in the chair, “happiness extends as far as contemplation does. So those who contemplate the most are most happy. But so far you have described him quite generally, and I still don’t know much about the Philosopher. How would I recognize him?”

“Recognize him?” I wasn’t sure what this meant. I thought of robed scholars and monks in cassocks. I thought of pale experts in government think-tanks. I wondered what it looks like to be close to the gods. “I suppose you could only recognize him by his…virtue?” I ventured. Was this an adequate answer? Somehow it seemed right.

“What do you mean?”

“In the Ethics, the Philosopher comes at the end of a long list of virtues. And several times you say that ‘virtue and the good man measure all things.’ So wouldn’t the Philosopher, the true contemplative, have all the preceding virtues – magnificence and a great soul – and wouldn’t we recognize him as somehow being more complete?” I remembered something else I had read: “And…maybe we would also recognize him by his strangeness?”

“Ah yes,” said the old man, “you are correct that we should recognize him by his virtue, but only if we are looking for virtue ourselves. I would not be surprised if the truly happy man seemed to most people a strange person – since most people judge by externals.”

Aristotle took another drink and adjusted his robes. We sat for a moment quietly. I did not know what to expect next, since we had discussed both Democracy and Philosopher, though I wasn’t certain I’d given a very good explanation of either. “More wine?” I asked.

“Yes. Thank you,” he said, handing me the nearly empty mug. As I filled it, he began again. “We have now considered two of the vague terms in your question. You, I think, have discovered that you need a little more study of history and a little more observation before you can speak about Democracy. As for your description of the Philosopher, it is good but theoretical. You told me about it as something outside your own experience. You would do well to look at your own life through the lens of what you said. Are you virtuous? Are you happy? Are you close to the gods? And,” – here he looked at me more intently – “this brings me to the last of the unclear terms in your question.”

“Which term?” I asked. I wasn’t sure what we had missed. My question was as short as I could make it.

“Possible,” he said. “You asked is it possible to be a Philosopher in a Democracy. This indicates to me that your question is not merely academic. In fact, your question is quite personal. This subject interests you because you want to know if it is possible for you to be a philosopher in your democracy. This will change the way we seek an answer.”

I did want to know about the relationship between government and virtue generally, but he was right, I was anxious to see if there was any way to be truly contemplative in America. Both intellectual curiosity and a longing to be – what exactly? A better human being? – were at work. While reading the Ethics I was alternately hopeful then despairing about the possibility of gaining virtue. It took a while for me to realize I was hoping or despairing for myself.

“You’re right,” I said, “it is personal. I want to find an answer because, somehow, I sense that my life might depend on it.”

“Then we will try for a little scientific knowledge of your question in the short time that we have. For that, we will need to at least know some of the starting-points. Let’s begin by seeing your question in light of themes in my Ethics. Can you name a few of the main themes?”

“Yes,” I said. “At the beginning you wrote about the importance of being habituated toward virtue. Specifically, the government should be involved in education for the benefit of the citizens. Sometimes it sounded as if virtue wasn’t possible without direction from early on.”

“Habituation is crucial,” said Aristotle, “and what about pleasure?”

“Oh yes. Of course, that was another important point. You talked about pleasure a lot – and about happiness and amusement along with it.”

“So we have two necessities, conditions, in a sense, for virtue. I’m sure there are many more, but let’s find a third, just one more for our discussion.”

I couldn’t think of one immediately. I hesitated.

“Let me help, because you’ve already mentioned it. We’ll call it ‘the favor of the gods’ and then we’ll have three starting-points: education, pleasure, and the gods. We will take these three as general aspects of the Philosophical life and use them to begin an examination of your life. We are assuming that you live in a Democracy, but we use that term loosely. There is still a written constitution by which your government is guided?”

“Yes, we have a constitution,” I said.

“So at least the ‘rule by the people’ includes your ancestors. You will need to consider more about that later. For now, let me be the inquirer, and you may answer. What is the goal of education in your society?”

“To be a good citizen, I suppose.”

“And does being a good citizen mean being a Philosopher?”

“No. It means being able to follow the laws, to have a job and raise a family.”

I wasn’t quite comfortable with this answer. It seemed, like my previous trouble with ‘Democracy,’ to be unconsidered. “Actually,” I added, “I’m not sure what the goal of education is. I worry that education is about making money and about keeping us from asking too many questions.” This was cynical, but closer, I suspected, to the truth.

“And what pleasures are offered by your society?” he asked next, “What amusements do you all most engage in?”

“Television,” I blurted out. This was, after all, very true. I took a sip of wine.

“And does this pleasure support virtue? Is it promoted by the virtuous people you know?”

I thought about channels. The History Channel and YouTube. Netflix. Pornography and Sesame Street. Wasn’t television more complicated than a simple answer would allow? But it occurred to me that the diversity of television wasn’t so diverse. I wondered what this had to do with Philosophy.

“I think television is a broad pleasure,” I reasoned. “You can get out of it what you want.” I was being defensive. This wasn’t an untrue response, but it didn’t quite answer the question. I added, “Television isn’t the only pleasure. There are movies. And sports.” I tried not to think about movie screens being large televisions and about the fact that most Americans follow sports from their living rooms.

But Aristotle continued: “Tell me about the gods. Does your government promote, support or defend the worship of the gods?”

Again, another uncomfortable topic.

“We have a separation of Church and State,” I said, “the government defends the right of its citizens to worship as they want to.”

“But the government itself?”

“The government is…neutral…I guess.” Here was another dilemma it would take me a long time to untangle. If Democracy is government by the people, and the people are religious, why wouldn’t the government be religious? And was ‘religious’ even the right word? I suspected the answers were buried in a whole chain of historical events that I wasn’t aware of. The confusion in my head must have appeared on my face, because Aristotle asked,

“What are you thinking?”

I tried to collect myself, but I was frustrated.

“I’m thinking that it must be impossible for a Philosopher to live in a Democracy.”

“Why?”

“Because,” I said, “virtue requires education. Obviously, I live in a society that does not educate with the highest virtues in mind. Like you said, ‘it makes no small difference whether we form habits of one kind or another from our youth.’ You said it makes all the difference. And, you said ‘it would be silly and childish to work and exert oneself’ for the sake of amusements. But that is exactly what we do. We work all day and go home to watch TV. I think we are ‘injured rather than benefitted’ by our amusements. Our pleasures are manifestly not what the virtuous man would choose for himself. And besides this, there is nothing in my society which would make me aware that I could be close to the gods, let alone that there is something divine present in me.”

“I disagree,” said Aristotle calmly, as if he wasn’t aware how frustrated I’d become.

“You disagree?” I asked. I assumed he would congratulate me on reaching some kind of detached enlightenment about my culture, but instead he was going to correct another flaw in my reasoning.

“Yes. I disagree. Your words just now were ‘it is impossible for a Philosopher to live in a Democracy,’ but then you tried to support this by arguing that a Democracy cannot produce a Philosopher. These are radically different ideas. Perhaps your argument is correct: a Democracy cannot produce a Philosopher. But we still haven’t answered your question, namely, can a Philosopher live in a Democracy. Do you see the difference?”

“The difference is…” I searched for the words. The conversation had taken another unexpected turn. “Well in any case, the Philosopher is not going to get any support from his Democracy,” I said. But this seemed a rather childish response.

“Precisely. But this doesn’t necessarily mean that Democracy will prevent a man from becoming a Philosopher or cease feeding and clothing him. We have only demonstrated that Democracy and Philosophy are incommensurable, not that they are mutually exclusive.”

“But won’t it be much more difficult to contemplate in a democratic society?” I realized as I said this that ‘much more difficult’ was far from ‘impossible.’

“A virtuous life requires exertion. What has changed?” he asked.

“The amount of exertion,” I laughed darkly.

“And you were hoping for an easy path?” Aristotle returned, “And if not that, then at least an easy excuse not to become a Philosopher?”

I looked up at the old man. He fixed me with a knowing stare as if he saw all along what was only just dawning on me. I’d asked my initial question sincerely, but I’d already half assumed that the answer was ‘no,’ that Democracy was opposed to Philosophy. I would then have both the praise of tackling the question and the privilege of resigning myself to a life of lesser pursuits. I imagined the universe patting me on the back, saying you did your best, but there was nothing for it. You lived in a Democracy. Extra credit, though, for thinking along the right lines…

“There are many ways a Philosopher can come to be in a Democracy,” said Aristotle.

He seemed to have noticed the change in my mood. He was now looking at me with less intensity. “The Philosopher can move or be moved to a Democracy. Or Democracy can overtake the place where he lives. In any case he will still have as his guide the thought of things noble and divine. Your case is different. You have been raised in a Democracy and have come to the idea of Philosophy by something from outside it. Nevertheless, you have been ‘captured’ in a sense by the idea of the contemplative life. It is possible that you will now never be completely happy unless you can finish your life as a Philosopher. Surely, as I have said, where there are things to be done, the end is not to survey and recognize them, but rather to do them.”

“How?” I asked.

“You must try any way you can of becoming good. Think back on some of the things we’ve been discussing.”

We had covered a lot of ground in a short time, so I wasn’t sure where to begin and my response was slow at first. “Well…we said that Democracy isn’t the best or worst form. So that means while the philosophical life isn’t being promoted, it isn’t necessarily being condemned. Democracy cannot honor philosophers, but it might at least ignore them. Philosophy would seem strange, but not hostile. And perhaps…”

A new thought struck me. “Perhaps a Philosopher could, well, hide in a Democracy? Maybe his contemplation would be less disturbed, if he could find some kind of balance. Friendship and Justice are less frequent, but contemplation needs only those few friends who can support it. And injustice might be an opportunity for true Philosophy to be demonstrated.”

“How?” he asked.

“Either in making wise laws to correct injustice or in bearing injustice patiently – or, philosophically.” I needed to think about this some more. I wasn’t sure what I meant. But I suddenly saw Democracy as something in flux while Philosophy was something beautifully immobile. This wasn’t an encouraging thought exactly, but maybe one I could come back to.

“And what about those supports for contemplation that you lamented were not available? Our three prerequisites were education, amusements or pleasures, and the favor of the gods. You argued that these prevented Philosophy.”

I considered this. “In a Democracy there are bound to be many kinds of education. I will have to find one – or make one? – that promotes contemplation. And I guess that even though the main sorts of amusement are rather mundane, we are not forced to engage them. No one is making me watch television…it’s just…a habit.” Perhaps Democracy and Philosophy could coexist, but a good education and the habit of watching TV were certainly incompatible. This thought distracted me until Aristotle interrupted with his next question.

“And the gods? How will you gain their favor?”

How would I gain their favor? I suddenly remembered that America had produced a lot of religions. Should I choose one of those? But, for the Philosophical life, wouldn’t it be best to find a religion that came from a Monarchy rather than a Democracy? This was not an easy question.

“I’m going to have to give it more consideration,” I said.

“I think that as you engage in the activity closest to the gods, the gods will guide you,” the old man said wisely, “If you are straining every nerve to make yourself immortal, they will help you to live according to whatever in you is most divine.”

“I hope so,” I said, sincerely.

Aristotle took one more drink of wine and set down his mug on the bookshelf next to the chair. “You would do well to keep your question foremost in mind over the next few years. Since you live in a Democracy, you will perhaps, as you said, have to make your own education. If you happen to find anyone superior in virtue, be sure to follow him. And remember to attend to both experienced people and to reason. There are many tools and many guides around you, if you care to find them.”

As he was speaking, my mind began to drift. It had been a long day; I was tired. I thought of stars in distant uniform rushing paths, and dodecahedrons resting on cubes comprehended in spheres, and Socrates offering a prayer to Pan. I thought of every activity having its proper pleasure, and I wondered what the proper pleasure of striving for Philosophy in a Democracy might be.

“Will I ever find that pleasure?” I said aloud without meaning to.

There was no reply.

My reclining armchair was empty; Aristotle was gone. I wondered if I had been asleep, dreaming. But there was a stir in the air, as if someone had just walked through the room. And an empty mug on the bookshelf…