The Power of Daffodils

Wordsworth and his contemporaries sparked an artistic revolution, the effects of which we're still feeling.

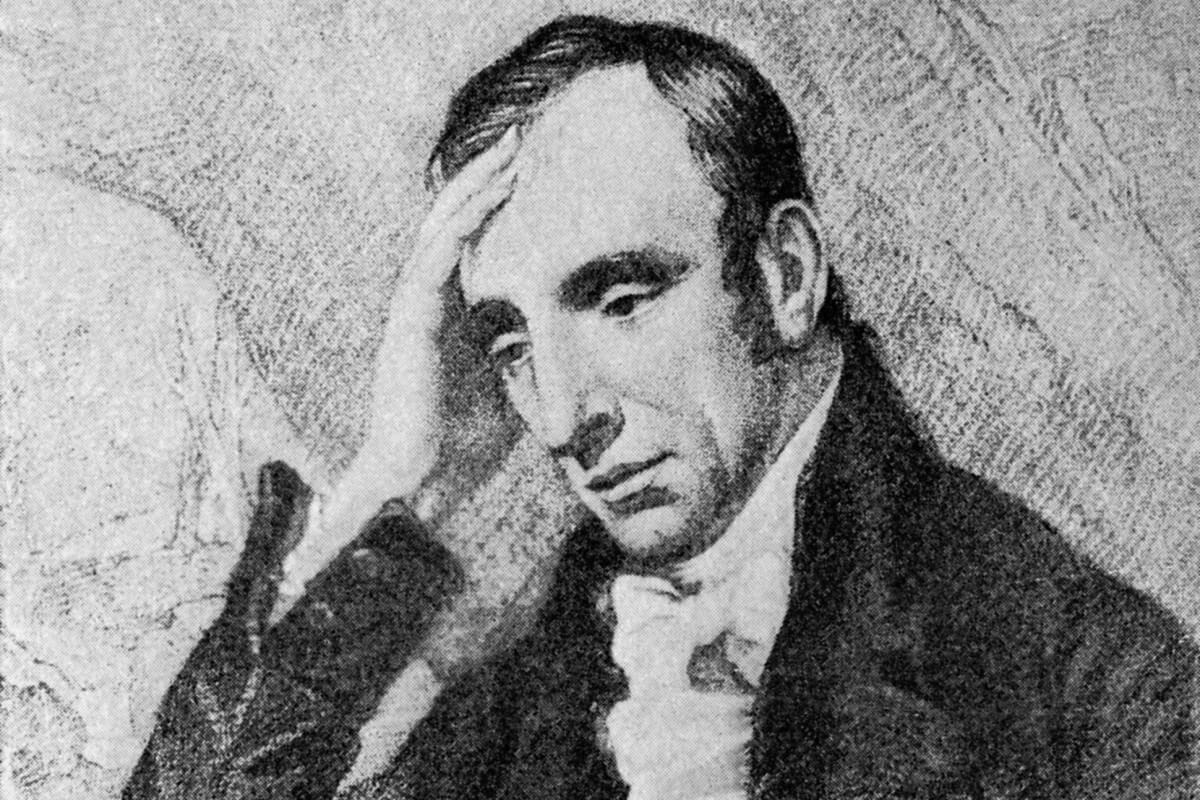

Have you ever read “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud,” William Wordsworth’s famous 1807 poem about the daffodils? It is worth quoting in full, and for a reason that you may not have considered:

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them danced; but they

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:

A poet could not but be gay,

In such a jocund company:

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

What wealth the show to me had brought:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

Pretty, is it not? It has beautiful scenery, a relatable persona who enjoys a bracing nature walk, and an optimistic, hopeful tone. Best of all, brevity and engaging rhymes allow this sing-song ditty to be easily memorized by fourth graders preparing for end-of-year recitations.

Is there anything else going on here that casual readers might be missing? Surely England’s greatest 19th century poet was attempting more than sweet nursery rhymes for children. In fact, Wordsworth was demonstrating a revolutionary theory of poetry that would eventually color everything attempted in the name of art.

Wordsworth had explained his theory in 1801 in a preface to Lyrical Ballads, a collection of poems he wrote with colleague Samuel Taylor Coleridge. He said:

“Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings. It takes its origin from emotions recollected in tranquility.”

In other words, an artist’s emotions are the proper source of poetry and of whatever truth poetry can communicate. Furthermore, the artist himself, as he recalls his emotional reactions, is the proper subject matter of poetry. Essentially, poetry is an artist expressing his feelings about his feelings.

When you look closely at the “Daffodils” poem, you can see Wordsworth consciously acting on this definition. Notice, for example, how the first two stanzas relate the persona’s experience in the first person. The poet himself is the main character of the piece. Notice, too, that the real subject matter of the poem–the “wealth” that the show has brought him, described in the final stanza–is the pleasure he derives from remembering the beautiful scene.

Wordsworth does more than assert a theory of poetry, however; he hints at a theory of knowledge.

Notice how the poet arrives at his emotional destination in the final stanza: “They [memories of the scene] flash upon that inward eye / which is the bliss of solitude.” The organ of sight and understanding, by which the poet knows Truth, is “inward,” or inside himself.

Furthermore, this “inward eye” works in solitude. Wordsworth’s followers would develop this last idea and eventually assert that the soul needs no instruction from man, society, or tradition, but is itself the sufficient source of Truth.

Romanticism, the literary movement that sprang from this idea, changed the history of Western art and culture. Its assumptions would have been unrecognizable to the great poets who wrote before 1800. In Paradise Lost, for example, John Milton proposed “to justify the ways of God to men.” In Hamlet, Shakespeare proposed “to hold a mirror up to nature.” These earlier poets used their art to seek knowledge and truth outside themselves; they sought a reference point against which to judge their impressions and instincts; they followed the ancient Greek admonition to “know thyself” in the context of a world where such a reference point existed. The Romantics swept all external reference points away and taught readers to “know themselves” as creators of knowledge, truth, and reality. Here was a revolution indeed.

As far as we can yet tell, the revolution was permanent, for pleasure and self-expression are still the language of art. To this very day, just about every songwriter, novelist, poet, or playwright who picks up a pen does so to expresses his own emotions, and his goal is to call up similar emotions in his audience, to foster a similar kind of self-expression. In other words, he follows the example of Wordsworth rather than the example of Milton or Shakespeare. He is a Romantic by default. For our part, when we say that an artist “has a voice,” we mean that he authentically expresses the truth he has found within himself. We are Romantics, too.

I think it amazing that we all learned to do this from a sing-song nursery rhyme about daffodils. Such is the power of poetry, and of ideas, which really do rule the world. It is helpful to remember, though, that even the most powerful ones are temporal: they replace older ideas at specific moments in history and are replaced in their turn by others. Perhaps the Romantic idea of art will give way soon to something else. Perhaps a return to Milton and Shakespeare is in the offing.

One can only hope.

Adam Andrews

Adam Andrews is director of Center For Lit and a homeschooling father of six. He and is wife Missy are the authors of Teaching the Classics: a Socratic Method for Literary Education, which presents a step-by-step method for teaching literature in grades K-12. Center For Lit offers curriculum materials and support for parents, teachers and readers at http://www.centerforlit.com">www.centerforlit.com