The Pains of Life-Long Learning

When can the steady, plodding, often frustrating, and rarely instantly gratifying pursuit of philosophy get a word in edgewise? Where can its spark alight in hearts besotted with flame retardant pleasures?

I recently re-read this article, written by Josh Gibbs in the winter of 2013. The title makes it seem like the article is about sports, but its particular point is about grades. The general point, however, has to do with the natural affections of the human hearts which have been entrusted to teachers in Christian classical schools to be shaped and molded into lovers of truth, beauty, and goodness: lovers of Christ.

Classical schools (and homeschools) have plenty of students who score very high on academic tests and whose aptitudes are capable of taking them into the upper echelon of scholastic achievement. Many of these students are hard workers. Many of them desire to please their parents and teachers. Surely they are successes by the normal measurements. Still, I often wonder how many of the brightest students leave their schools as philosophers; that is, as lovers of wisdom?

It takes far more virtue, far more self-discipline, far more courage, far more humility, far more self-understanding, far more prayer, far more fear, and far more trembling to be the kind of person who hungers and thirsts for truth and righteousness than it takes to be Summa Cum Laude.

The difficulty does not lie in the nature and affections of the students alone, either.

Teachers who love to teach are not necessarily, themselves, “lifelong learners,” the colloquial term Classical school marketing uses for “philosophers,” (which would sound a lot weirder in the marketing brochures). A good teacher loves to see his students learn what he knows and loves, and this is a valuable and indispensible quality. But the ability to reproduce one’s own learning in others doesn’t exhibit “lifelong learning” in and of itself.

The teacher who is a philosopher learns her students each year and figure out what makes each of these incomplete human souls tick, turn, hunger, and thirst. And she has to stay on her toes because even though inertia is a powerful force of nature, the overwhelming energy of youth, combined with its malleable frame, greases the souls of these burgeoning disciples.

Teachers who are philosophers also learn themselves. They seek out reflection, wise counsel, and even the observations of their students in order to discover the helpful and the harmful habits, the inconsistencies, the lacunas and lingering ignorance; the vices that beset us and sunder us from the path of wisdom.

Teachers who are philosophers also learn all kinds of things, including some things entirely unrelated to the subjects they teach.

Some teachers have one or more of the qualities of philosophical pursuit but few possess all of them, and of those who do, fewer still are naturally drawn toward the disciplined life required to hone and refine these philosophical gifts. Many, perhaps most, have to struggle along after them.

At least one of the causes is circumstantial. We live in an age that doesn’t prize such qualities. There are no external rewards awaiting those who would be philosophers. Teachers who pursue philosophy as a concomitant; or better, consubstantial; calling with teaching are more likely to find themselves out of place in the world; or more likely still, find that “with much wisdom is much grief, and he who increases knowledge increases sorrow.” Of course the difficulties are only part of the story, and I’ve mentioned before the pleasures that philosophy affords those who pursue it. But the pleasures are often solitary and finding others willing to linger in them calls to mind another of Solomon’s sayings, “one man among a thousand I have found, but a woman among all these I have not found.”

But supposing these difficulties are surmounted, there remains the difficulties of the students, whose attention, affections, aptitudes, and aspirations are all too easily captivated and preoccupied by the diversions (some of them quite good, even necessary) of sports, video games, social media, social gatherings, part-time jobs, romantic relationships, etc.; not to mention the general ennui generated among a generation glutted in overstimulation of the senses and baser desires.

When can the steady, plodding, often frustrating, and rarely instantly gratifying pursuit of philosophy get a word in edgewise? Where can its spark alight in hearts besotted with flame retardant pleasures? “What profit has a man from all his labor in which he toils under the sun?”

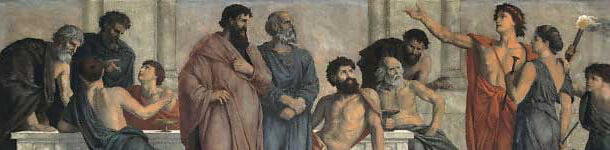

In Meno Plato offers several ways virtue, or excellence, may be taught and learned. Although the dialogue ends in aporia, one of the “right opinions” that Socrates entertains suugests that virtue is a gift from the gods. Augustine, in his dialogue De Magistro, follows a similar train of thought, but concludes that whatever men know, they know by virtue of Christ, the Teacher within Who reveals knowledge in conjunction with external signs. Both of these philosophers acknowledge the incommunicability of wisdom from one human soul to another unmediated by a third party. There is a Trinitarian gesture of philosophy if ever there was one!

Perhaps as we seek to cajole hearts and minds toward the call of lifelong learning, we would do well to recall that, in the midst of all of our dialectical signs and symbols, the best stimuli still require a personal revelation, however small, for souls to become enflamed. Perhaps it makes it more marvelous to the angels who gaze upon us that any soul can still be lit when it has been doused, like Elijah’s offering at Carmel, thrice over in the waters of the present age’s distractions.

Is not the hope of one incandescence enough to satisfy a lifetime of striking out?

Joshua Butcher

Joshua Butcher is married to the indefatigable Hannah and is the father of four festive boys and one gregarious girl. He began teaching Classical Christian Education in 2010 and continues to climb further up and further in. Joshua aspires to be capable of teaching an entire rhetoric curriculum using only Homer and Shakespeare.