More Than Human

"Belief" has changed meaning over time due to the modern scientific mindset. How does this impact the way we treat each other?

It should be of urgent concern that the meaning of the English word “belief,” an indispensable lens for both the confession of faith and cultivation of wisdom, has profoundly evolved. In his work Faith and Belief, Wilfred Cantwell Smith outlines this dilemma:

A major shift in the meaning of the English word “believe” . . . has proven of massive consequence and fateful significance. . . . The word “believe” . . . began its career in early Modern English meaning “to belove” . . . to hold dear, to cherish . . . To believe a person, or to believe “in” . . . was to orient oneself towards him or her with a particular attitude or relationship of esteem and affection, also trust—and more earnestly, of self-giving endearment.

While this meaning held sway for more than five hundred years, in contrast the Enlightenment has managed to steer us toward something akin to “the mental assent to the truth, the existence, or the reliability of something.” Thus, the term has moved from being a kind of social-ethical judgment between two or more people to an impassive-rational judgment about a proposition. This once subject-ive term has bent under the weight of the object-ive scientific method, diminishing the world of interpersonal subjects to a world of mechanical objects.

In an age where the scientific method has claimed a monopoly on truth, the church has taken heed and submitted, lest we make unverifiable claims about the unverifiable stuff in the Kingdom of God. The deepening of faith, then, becomes a process of gathering facts to convince oneself that the doctrines of Christianity are sound deductive proofs. Believing something in your heart is silly, since everyone knows that belief is something we do with our intellects, not our hearts, right?

Never mind that this definition (limiting belief to the intellect) devalues any trace of wonder, expels any ethical or aesthetic dimension, and incapacitates the experiential side of belief. What is most conspicuously absent from such a meaning is its explanatory power. The belief, say, that dogs make for better pets than cats, is a profound conceptual mystery, charged with experiential data of various kinds and intense emotional import, interconnected and formed through a myriad of other beliefs and desires. “Mere beliefs” are not mere words, nor a collection of mere facts.

The modern definition of “belief” has unfortunately reduced all knowledge to what C.S. Lewis refers to as “scientific language,” that medium of speech with which most experience cannot be adequately described. The definition should reflect that the whole of human experience is involved in our acquisition of beliefs; otherwise, we might find our description to be sub-human, fit for beasts, or worse, fit for machines.

Psychiatrist and Oxford scholar Iain McGilchrist, affirms that the brain’s two asymmetrical hemispheres offer two different lenses for understanding reality. In his seminal work The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, McGilchrist notes that the left hemisphere sees through a hyper-focused, narrow lens that gazes upon a thing’s parts in objectified, mechanized isolation; the right sees through a broad, imaginative lens that gazes upon the whole in associative integration. In fact, so broadly imaginative is the right hemisphere that, with certain functions like language, it can operate not only out of “its own preferences, but . . . can also use the left hemisphere’s preferred style, whereas the left hemisphere cannot use the right hemisphere’s” (p. 41).

But, instead of the two cooperating, McGilchrist contends that the left hemisphere’s narrow vision has come not only to predominate our view of reality but it has also effectively blockaded much of the right hemisphere’s necessary integrative role for seeing “the bigger picture” (p. 43). Hence, “An increasingly mechanistic, fragmented, decontextualised world, marked by unwarranted optimism mixed with paranoia and a feeling of emptiness, has come about” (p. 6). As a result, we may “have to revise the superior assumption that we understand the world better than our ancestors, and adopt a more realistic view that we . . . may indeed be seeing less than they did” (p. 461).

McGilchrist relates a story by Nietzsche: There was once a wise Master, selflessly devoted to the good of the people, whose kingdom was eventually usurped by one of his greedy emissaries. The narrative ends with the tyrannical rule of this former emissary, leading the kingdom to self-destruction. McGilchrist comments that, although the hemispheres should cooperate,

At present the domain—our civilization—finds itself in the hands of the [left hemisphere], who however gifted, is effectively an ambitious regional bureaucrat with his own interests at heart. Meanwhile the [right hemisphere], the one whose wisdom gave the people peace and security is led away in chains. The Master is betrayed by his emissary. (p. 14)

The outcome looks something like this: In gazing upon a beautiful backdrop, one can concentrate so hard on a particular feature of it that one experiences no beauty at all. In the same way, our modern definition of belief is only suited to gaze upon the parts in narrow, isolated focus, leaving the bigger picture unseen.

Sadly, this obsession with isolated, propositional facts might very well produce the dysfunction of the left hemisphere that could lead to such a lamentable condition as Darwin himself professed:

My mind has changed during the last twenty or thirty years. . . . I cannot endure to read a line of poetry. . . . I have also almost lost my taste for pictures or music. . . . My mind seems to have become a kind of machine for grinding general laws out of large collections of facts, but why this should have caused the atrophy of that part of the brain alone, on which the higher tastes depend, I cannot conceive. . . . The loss of these tastes is a loss of happiness. (Autobiography)

We are not only lacking in imagination, we are effectively adapting our brains to disarm it. Until we are prepared to allow the imagination to rightly lead us in this renewal of the image of God, I contend that we will always be working at a severe deficit.

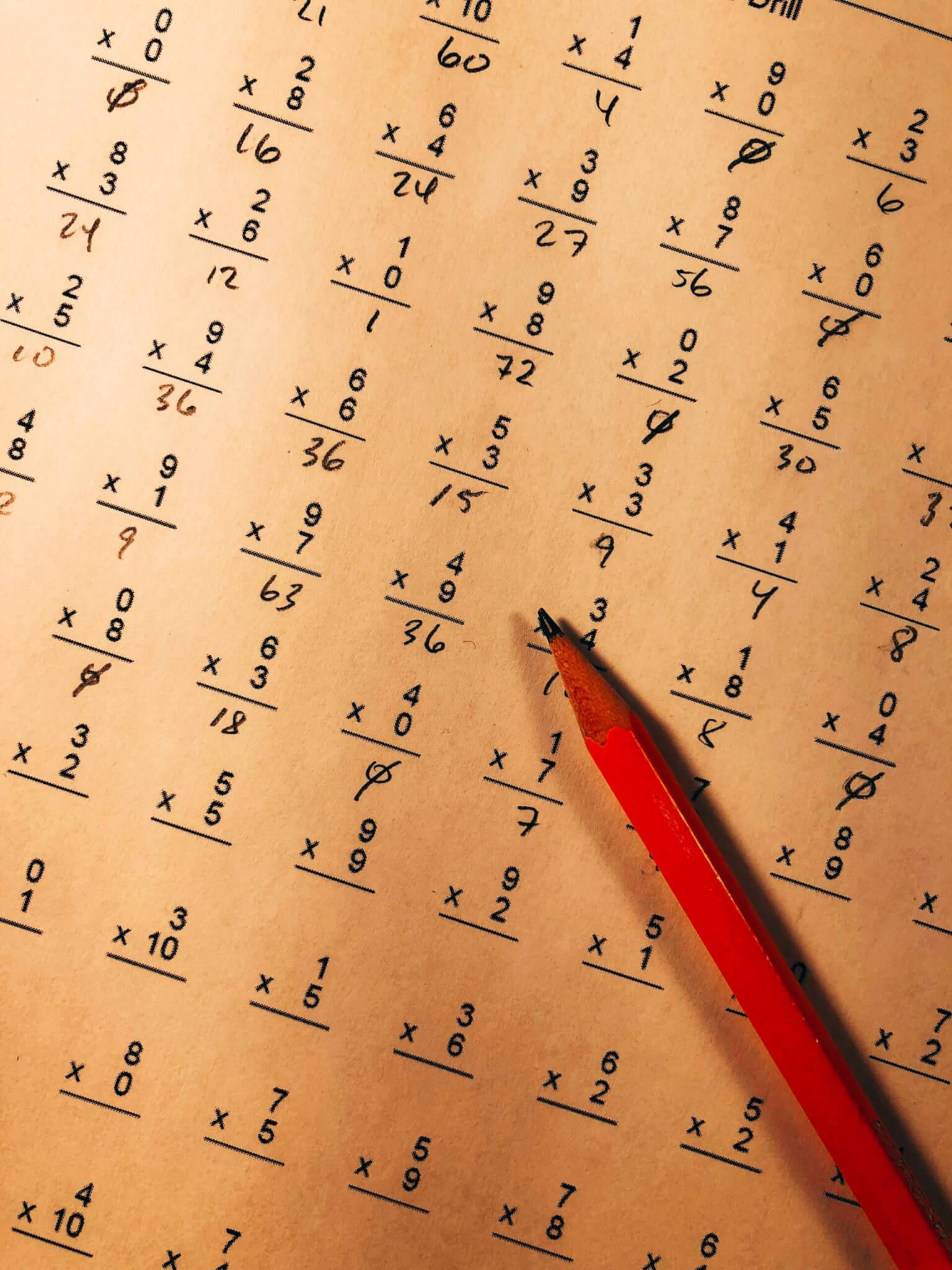

As educators, then, we too must depend upon a lens that is able to illuminate what is unseen. We must value quality of integration over quantity of information, rehearsing truth over memorizing facts, building character over building resumes, life prep over college prep, acquiring spiritual habits over acquiring cumulative knowledge, and finally, good virtues over good grades. In other words, the things we should most concern ourselves with are not subject to scientific verification. We will set our students free when we can learn to treat them as multifaceted, thinking, feeling, acting, loving, unique human beings rather than mass-produced, systematically manufactured machines.

What we celebrate ultimately indicates what we value most, and so long as standardized tests and perfect grades remain our most cherished prize, we will continue to find ourselves and our students shackled by life-draining constraints. Mechanistic, numerically-quantifiable measurements are helpful tools for evaluating the worth of a machine, but they are in no way maximal measures of the worth of human beings, who, as Lewis said, have fully evolved from “being creatures of God to being sons of God” (Mere Christianity), from human to more than human.

What would it mean to treat our students as more than machine, even as more than human? To “grade” them as more than human? To point them to something that is more than human?

Aaron Ames

Aaron Ames currently teaches Rhetoric, Logic, and Literature at Trinity Christian Academy, a classical Christian school located in Lexington, KY. He received a BA in Letters (Great Books Program) from the University of Oklahoma and two MA's, one in Biblical Studies, and the other in Theology and Philosophy, both from Asbury Theological Seminary.