Memoria: Handmaiden of Rhetoric

Our era is dismantling millennia of incarnated memories with increasing fervor and speed—“old” books are considered irrelevant, so much so that it can be difficult to find classics in local libraries or school curricula; monuments and artistic creations, some of which have withstood the ravages of decades, if not centuries, are toppled in the name of social progress; beautifully crafted belongings, once meaningful heirlooms, are jettisoned in favor of the newest machine-made decorating fads and end up in dusty thrift shops.

Lately, all these sorts of things smack too much of outdated ideas and eroding beliefs. In many ways, in the twenty-first century, they just feel like too much work to understand, let alone maintain. In a fit of prejudice against such physical, mental, and spiritual effort, we’re discovering ourselves to be a people who favor forgetfulness. We like to think we embrace a spacious and airy nothingness in which we’re able to continually reinvent ourselves rather than wrestle with the memories of what has been, where we come from, and who we really are.

Several times, in defense of minimalism, I’ve heard the Latin word impedimenta brought up. This was a military term for the baggage train that followed troops as they campaigned. English derives its word “impediment” from it: something that hinders us from doing or getting what we want. At face value, it seems true. After all, a baggage train, heavily laden with the supplies needed to support an army, slows things down, reducing the efficiency of military maneuvers. Surely it’s best to rid ourselves of impediments, right?

Yet, whenever I’ve heard this, I’ve found myself thinking: Without that baggage train, the army would be unable to fulfill its purpose. Without food, without supplies, without armaments, without all the myriad little things armies need to sustain themselves, there can be no campaign, and, ultimately, no victory. Although the baggage train requires extra thought, work, and time, there is little chance of success without it. In a similar way, though these memories we seem so anxious to eliminate might appear to be impediments, in reality they are like the baggage train that provides essential elements to successful human enterprise.

As classical educators, we place heavy emphasis on the art of Rhetoric. I’d go so far as to assert that Rhetoric, as the mapping out of the processes of persuasive speech, expresses the essence of what happens in all human creative endeavors: the same steps that go into making an excellent piece of communication also are at work in the creation of a painting or sculpture, a composition of music, an architectural design, a mathematical proof, or a scientific theory or invention. The “form” of the process of Rhetoric remains the same, while the “material” in which it’s employed may differ.

This is a reasonable claim, for writing is often thought of as “thinking out loud”: the thought that would go into a speech mirrors the thought process that goes into creating any artifact. And, no matter the material incarnation, each of the things mentioned above is a form of communication. Given that speech is perhaps the single greatest characteristic that sets us distinctively apart from other creatures, this makes sense: We are creators in ways that none of the other creatures can rival; we have speech, with its natural underlying foundation in Rhetoric, and they do not. Creativity is human expression. The process of Rhetoric incarnates human creativity.

We should therefore pause, long and hard, with respect to our society’s quest to rid itself of the impediments of Memory, because Memoria is itself one of the five canons of Rhetoric. Although Memoria seems often relegated to an afterthought when we teach Rhetoric, we need to ask ourselves a pivotal question: “What happens to Rhetoric when we obliterate Memory? Can Rhetoric sustain the loss of this canon, and therefore can human creativity withstand its absence?” The answer is “No.” No work of art, literature, philosophy, science—not any human artifact ever—has been brought forth by human beings out of whole cloth.

No doubt, it’s hard work to recollect, cherish, and contend with memories and Ebenezers. Yet classical educators, if we have any hope of truly instructing our students in what it means to be human—that is, creators—must do just that.

Let me explain further by reaching back in time to one of the earliest collections of Memoria we’ve been privileged to inherit from those who came before us, who preserved such things for our edification:

These are the researches of Herodotus of Halicarnassus, which he publishes, in the hope of thereby preserving from decay the remembrance of what men have done, and of preventing the great and wonderful actions . . . from losing their due meed of glory.

-Herodotus, Histories (tr. George Rawlinson)

Here, in the proem to his book, written ca. 425 BC, Herodotus became worthy of the descriptor “The Father of History.” And what is history if not archived Memory?

Herodotus’ written narrations have often been criticized for inaccuracy. Since we live in a time in which perceived error is justification for obliteration, to most people Herodotus is not simply irrelevant, he is invisible. He might as well have never existed. Given the above-mentioned standard, however, we can and should point out that Herodotus has been proven right more than once. It was he, after all, who told the fantastic story of fox-sized “ants” spreading gold dust in their digging, a tale corroborated when a French explorer in the 1990s discovered a Himalayan marmot that did—and still does—literally spread gold dust. The confusion was possibly caused by mistranslation of the Persian term “mountain ant,” similar to “marmot.” It was also Herodotus who told of Phoenician navigators who reported they saw the sun to their right as they sailed west. We now realize this tale may reveal that the Phoenicians reached the Southern Hemisphere, circumnavigating Africa. Just recently, archaeologists have excavated an ancient Egyptian ship, called a baris, whose construction matches the description which Herodotus rendered. Historians have dismissed Herodotus’ account of such ships as fabrication, but they must now give credit where credit is due.

Our societal leanings toward chronological snobbery would have us toss The Histories into the bonfire with all our other passé, so-called “impediments.” And yet, when we do that, how much understanding of the world, of the character and deeds of men, of ourselves as standing upon their shoulders do we lose? It’s an inestimable loss.

All this brings us to the salient point, one that Herodotus savored: Preserving memory matters; not only that, there’s glory in it. It isn’t always the glory arising from mighty conquest. Nor is it necessarily the glory of magnificent pomp and circumstance. It’s the glory of human existence and creativity. The ancient Phoenicians did attain a feat that for centuries after remained elusive for fearful navigators. The Egyptians did build ships with novel construction, the likes of which have not been seen in thousands of years.

Aristotle reputedly said, “Memory is the scribe of the soul.” The source for the quote is elusive, but it seems to have been attributed to him since at least 1899 (Dictionary of Quotations, Rev. James Wood). Probably too poetic for Aristotle’s style, the phrase nevertheless summons an important truth: Memory records and stores the soul’s experiences. It does more than that, however. Thinking about the nature and role of the scribes in ancient civilizations, recall that across cultures scribes were an elite class with profound impact on governance—administering religion, law, and economics.

Scribes were also often closely associated with wisdom, and as such they were important in affairs of state as well as in interpretation of religious texts. In effect, scribes—through development of writing, codifications, explanations, and rituals—were what we might think of as gatekeepers of paideia, the Greek concept of education which can be understood as the passage of collective cultural memory from one generation to the next.

Herodotus was consciously a scribe, memorializing the actions of men so that we, the heirs to his memoirs, might receive knowledge of what it means to be human. Furthermore, as Herodotus’ memorializing was to humanity, so too is our personal memory to our own souls. Memory is our scribe. She is the gatekeeper of our own personal paideia: the education of our soul toward creative communication with our world, others, and ourselves.

In his Confessions, first published in AD 398, St. Augustine wrote, “Whatever be in the mind is memory.” It’s important to realize, as Herodotus teaches us, that memory is comprised of the thoughts and deeds that flow from the creative wellspring of human beings—from their rhetoric. The oldest extant Latin book on rhetoric, Rhetorica Ad Herennium, once attributed to Cicero, adds another nuance: “Nunc ad thesaurum inventorum atque ad omnium partium rhetoricae custodem, memoriam, transeamus,” meaning, “Now let me turn to the treasure-house of the ideas supplied by Invention, to the guardian of all the parts of rhetoric, the Memory” (tr. Harry Caplan).

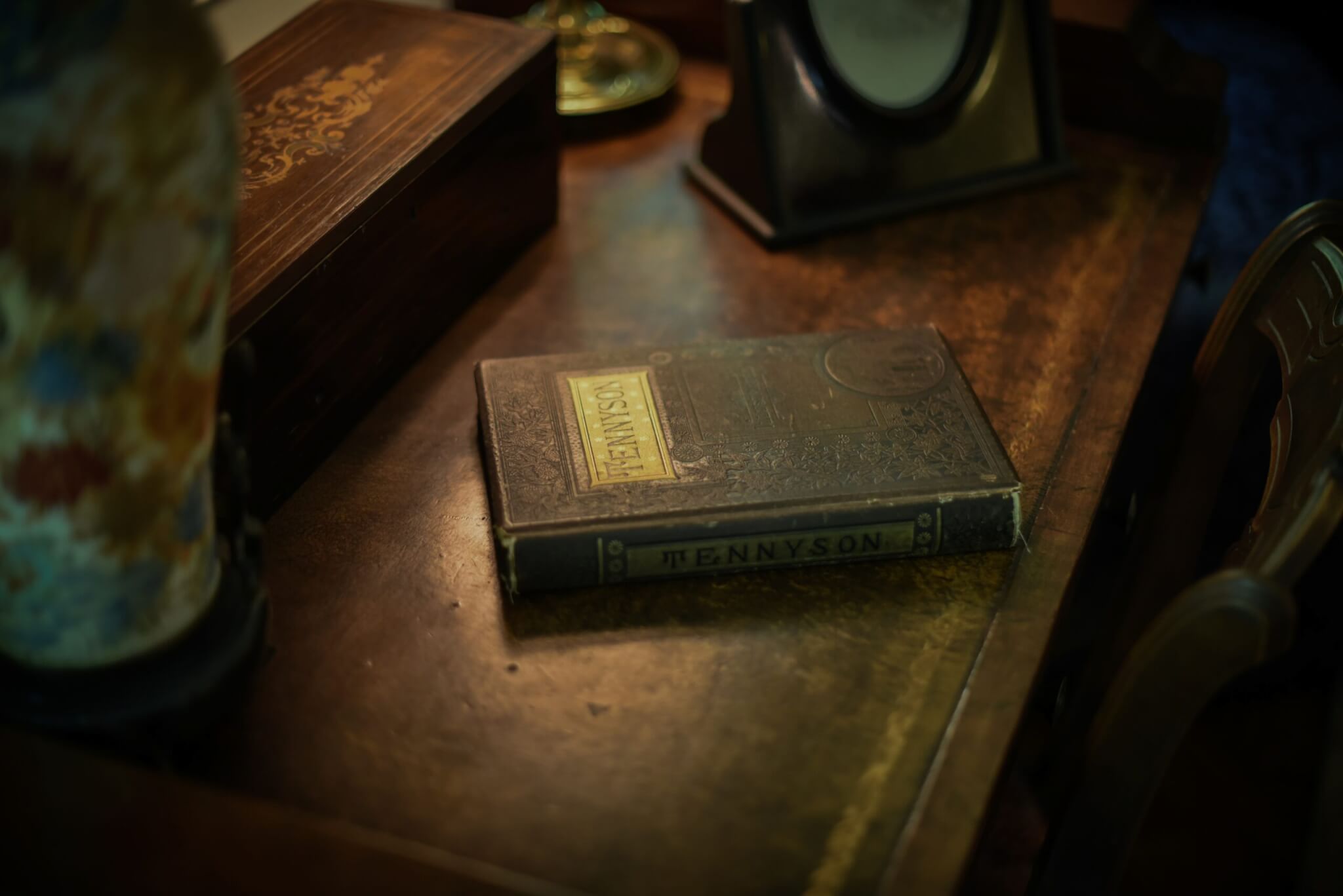

The canon of Memoria is indeed the guardian, the gatekeeper, of all parts of Rhetoric. This is perhaps why she, of all the canons, can be the most resistant to analytical definition. While Inventio, Disputatio, Elocutio, and Pronuntiatio can often be enunciated and transmitted to students without great difficulty, there is an air of mystery to Memoria; she is one thing—a deceptively simple canon in her own right as the memorization of a speech, for example—and yet she is so much more. A muse, she whispers, “But remember this . . . ,” at which prompting we return to the treasure-house and fine tune our invention, arrangement, and style, no matter the realm in which we are working (explaining, drawing, sculpting, exploring, or inventing). And, in the act of delivery, she descends, reminding us of the perfect anecdote, action, or adjustment for our particular audience in a particular moment. As the poet Tennyson writes in his Ode to Memory, she is an inspiration:

Thou who stealest fire,

From the fountains of the past,

To glorify the present; oh, haste,

Visit my low desire!

Strengthen me! Enlighten me!

Memoria is present in and around the other canons, the handmaiden of all Rhetoric. At her best, she is a storehouse of information, impressions, and evocations; a tabernacle of tradition; a hallmark of identity; a master imitator; an adept at driving investigation and exploration; and the final vehicle for successful—and one hopes beautiful—delivery of the fruits of rhetorical endeavors. At her greatest, she is capable of wielding pathos, logos, and ethos with stunning grace and precision.

While the other canons are guided by us as we practice the art of Rhetoric, Memoria inverts the process and guides us through them. She is handmaiden to the riches of our own souls as we—exercising the nature we inherit imago Dei—live as creators.

As we work with our students through a period in which the artifacts of human Memoria are being fiercely torn down in favor of invasive, prevailing trends, classical educators should be encouraged to not only instruct their students in the glory of this handmaiden of Rhetoric, but teach them to resist, as Anthony Esolen puts it in his book Out of the Ashes, the zeitgeist of our times: the assault of Memory in a “cult of erasure and oblivion.” Classical educators beware. If our society succeeds in annihilating Memoria, the handmaiden of Rhetoric, we will handicap—and possibly amputate—that which is inherently crucial in what it means to be human: creativity.

Kate Deddens

Kate Deddens attended International Baccalaureate schools in Iran, India, and East Africa, and received a BA in the Liberal Arts from St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland and a MA in Mental Health therapy from Western Kentucky University. She married her college sweetheart and fellow St. John’s graduate, Ted, and for nearly three decades they have nurtured each other, a family, a home school, and a home-based business. They have four children and have home educated classically for over twenty years. Working as a tutor and facilitator, Kate is active in homeschooling communities and has also worked with Classical Conversations as a director and tutor, in program training and development, and as co-author of several CCMM publications such as the Classical Acts and Facts History cards. Her articles have sporadically appeared at The Imaginative Conservative, The Old Schoolhouse Magazine, Teach Them Diligently, and Classical Conversations Writers Circle.