The Limitations of Language

Why does Jesus speak primarily in story and metaphor?

Similes and metaphors are our bread and butter at Center For Lit. After all, figurative language gives literature its beauty and its power. It’s one of the things that separates Homer’s Odyssey from an encyclopedia article. Given the choice between a police report and a detective story, I would always rather read the latter, mostly because of the beauty of language that shows rather than tells, that deals in pictures rather than literal explanations.

When it comes to matters of faith, however, I’m conflicted. It seems to me that direct, literal explanations of the things of God would be a lot more helpful sometimes.

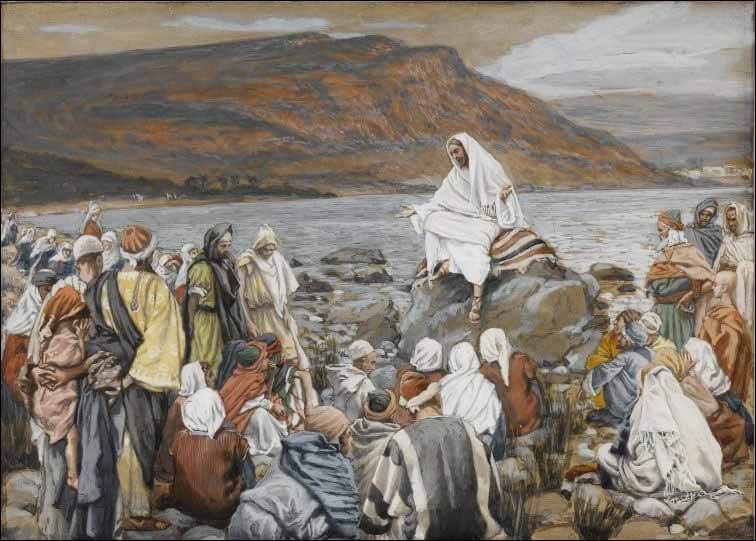

Take the conversations of Jesus with the crowds in the New Testament, for example. Why does He always seem to be avoiding their questions, answering in cryptic language? Why does his point always seem imprecise and hard to understand? At times, His words even seem calculated to confuse his listeners. An example from John chapter 12 illustrates the point:

Crowds: “Who is this Son of Man?”

Jesus: “You have the light a little while longer.”

What kind of answer is that? If the truth that Jesus came to reveal is so important, and if the crowds are asking for it directly, why doesn’t He just tell them? In declining to provide direct explanations of His ways, Jesus seems to be underusing the language. Aren’t the stakes a little high for a move like that? Why would He do it?

My reaction betrays the assumption that literal explanations are the most meaningful, but what if I assume instead that the stakes really are as high as Jesus said they were? What if I assume that with each enigmatic answer, Jesus is using human language to the fullest extent of its power to communicate the Gospel? What if He isn’t underusing the language at all? What if He’s overusing it, stretching it to its absolute limit – all the way to the edge of simile and metaphor?

This puts the thing in a new light. It could be that Jesus, in His conversations with the crowds, is attempting the most difficult teaching project in world history: explaining an infinite God to finite men using finite language.

It could be that out there on the edge of the infinite, words simply fail. Maybe that’s why Jesus instantly resorts to simile and metaphor when asked to explain the kingdom, or the Son of Man, or the Gospel. Maybe He knows that literal explanations are best suited for natural phenomena, but they are poor tools indeed for describing a supernatural invasion of the world.

The limitations of language illuminate more than Jesus’s answers; they also shed light on the questions themselves. After all, can we assume that the crowds have a better grasp of language than Jesus does? How can we be sure they even know how to formulate their question, much less say what they really mean?

On a literal level, the people’s question in John 12 is about the idea of the suffering Messiah. “Our reading of the prophets tells us that the Christ is an eternal victor,” they seem to say, “but you, while claiming to be the Christ, describe yourself as a loser who came to die. What kind of Messiah is that? We don’t get the concept at all. Who is this ‘Son of Man,’ anyway?”

But if language is the meager tool of expression that I have suggested, they could be asking for much more than a theology lesson. If, in any real sense, they represent the human race that Jesus came to save, they are stumbling in darkness in their hearts. Terrified souls, lost and alone. Perhaps the literal meaning of their question is a poor reflection of the real cry of their hearts for comfort and solace, for fellowship in suffering, for light in darkness. Perhaps their words simply fail them.

And so, stretching their language to its very limits, Jesus responds with a metaphor that makes more sense than any literal explanation ever could. “I am the light for your darkness,” He says. “You are not alone; I am here with you. Trust me; for regardless of your ham-fisted phrasing of the question, I am the answer that will satisfy your heart.”

If Jesus had wanted to give a literal answer, He could have said “the Son of Man is the real Messiah spoken of in the Prophets. You have simply misunderstood what they meant. Got the reference wrong. Not a king but a servant. See?” But such an answer would be beside the point, and He knows it. They don’t need a doctrinal refresher; they need a relationship with the God who never leaves us in our darkness, whose light drives all fear away.

Perhaps this is happening every time Jesus gives one of those enigmatic answers. I’ll take encouragement from this idea; for the abundance of such moments in the New Testament then testifies to the overwhelming greatness of God and His Gospel.

The glory of figurative language is to give us pictures where explanations fail. This is also the glory of the Incarnation. God cannot be described or explained; He must be seen to be believed. Knowing this, He came in a body, a picture – a fleshly metaphor, if you like – to comfort and convince our hearts. Though oftentimes we can’t even phrase the question, His presence in the world – his life, death, and resurrection – is the answer that we seek.

Words fail, but hearts understand.

Adam Andrews

Adam Andrews is director of Center For Lit and a homeschooling father of six. He and is wife Missy are the authors of Teaching the Classics: a Socratic Method for Literary Education, which presents a step-by-step method for teaching literature in grades K-12. Center For Lit offers curriculum materials and support for parents, teachers and readers at http://www.centerforlit.com">www.centerforlit.com