On Lent, Marshmallows, and Shelter-in-Place

Like it or not, a kind of Lent has greeted everyone this season, albeit in the forms of forced social-distancing and the compulsory self-denial of certain goods or activities. (Blessed are they who have trampolines?) For Christians who don’t observe the historic church practice, consider it a forced Lent. For those who do observe Lent, the recent weeks of sheltering at home serve only to extend or intensify the great fast. Regardless of one’s politics—regardless of the varied theories on the policies we’ve adopted to combat the Coronavirus—one thing is certain: we have all entered into a state of going without. This is hard and invites a good discussion.

Before we get to this discussion, however, it’s helpful to remember Lent is part of that qualitative vision of time called the “church calendar.” When the risen Christ made it clear that all authority on heaven and on earth had been given to him (Matthew 28:18), the Church responded as soon as she was corporately able with a new calendar. And in so doing, the Church guarded kairos, setting apart certain days and seasons from others, lest they become an indistinguishable mass of chronos, ticking life away one second at a time, ever scourging men onward to and for the next task. Instead of marking our lives with devotion to the cultic revelries of the Super Bowl, students might learn which celebrations matter most to Christian life, putting the “Saint” back into “Valentine’s Day,” for instance, or the “Hallows” back into Halloween. For a Christian institution of classical learning, the “Annunciation” should be a familiar day and Lent an accustomed season.

But how is a classical Christian school (or community) really supposed to think about Lent? Is it just a word, or does it constitute some form of participation? This question is vexing for some, and I’ve always found that talking about Lent makes rather uncomfortable conversation for evangelical parents and students. But our current situation of lockdown offers a unique invitation to defend the “great fast,” because it offers an invitation to discuss self-denial.

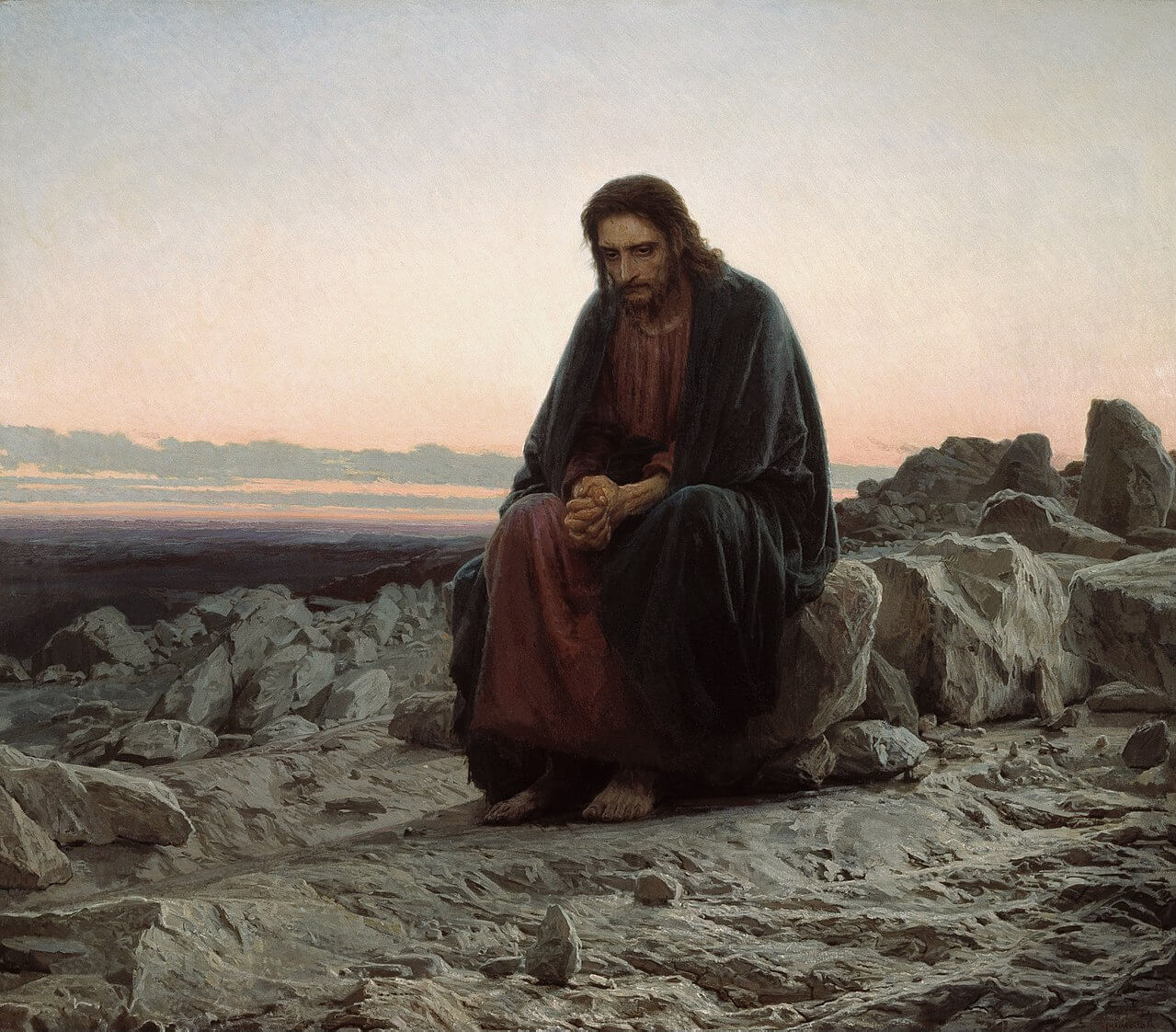

As a penitential season of the liturgical year, Lent is often marked by fasting, a word which for many is shrouded in mysterious and abstemious austerity. But fasting is an assumed discipline in the bible. “When you fast,” Jesus says, “do not be as the hypocrites.” In Matthew it says that after he was baptized, “Jesus was led up by the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil. And when He had fasted forty days and forty nights, afterward He was hungry.” (4:1-2). In Lent, the Church follows the example of Christ, who disciplined himself in the practice of prayer, fasting, and resisting temptation.

It was there in the wilderness that the devil asks him to make stones into bread to satisfy his earthly desire of hunger. But remember how Jesus responds: “It is written, Not in bread alone doth man live, but in every word that proceedeth from the mouth of God” (4:4). This is a profound statement of anthropology, about what a human is. Are we animals? Are we angels? David describes it as somewhere in the middle. “For thou hast made him a little lower than the angels, and hast crowned him with glory and honour. Thou madest him to have dominion over the works of thy hands; thou hast put all things under his feet” (Psalm 8). That we don’t live by bread alone isn’t just a testimony of God’s providence. It is a demonstration of our spiritual nature.

Put food in front of a hungry animal, and it will consume the fodder every time. But humans are not so bound by their appetites or instincts in the same way. The image of God is possessed with that stamp of divinity that may allow him to deny himself the pleasure of satisfying his belly in favor of some higher and more perceptive reason. Consider the famous sociological “Marshmallow Experiment” at Stanford in the 1960s. Researchers wanting to measure the effects of a principle called “delayed gratification” put hundreds of children between the ages of 4 and 5 to a simple test: they placed a marshmallow on the table in front each child and explained that each can have one now or two later. The researcher would then leave the room for fifteen minutes, and the film footage suggests that for some young souls those fifteen minutes were not unlike Christ in the desert with Satan at his elbow. Some kids physically covered their eyes with their hands to avoid giving into temptation. Some sang songs and talked to themselves (a wise intuition). And some simply yielded to temptation without struggle or resistance. After repeated returns to analyze the development of the children tested, what the study was ultimately purported to suggest was that the principle of “delayed gratification” correlated to success in many other areas of life later. Not to mention contentment and happiness.

But what is “delayed gratification” but another name for “short-term self-denial”? The ability to deny oneself something presently is then critical to success later. Doubtless, Chesterton would have laughed and said that we didn’t need Stanford professors to tell us what grandmothers, fairy tales, and the Bible told us long ago. But such is the modern world. We need to relearn everything all over again, with scientific verification to boot. But if modern Christians didn’t generally abandon the observance of Lent through fasting long ago, then perhaps we wouldn’t now be able to measure, for instance, the same divorce rate in the church as outside of it. Self-denial is simply what it to takes to do anything well, an essential ingredient of victory in any pursuit. But it also happens to be a special qualification in being a follower of Christ: “If anyone desires to come after Me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow Me” (Matt. 16:24). Why does Jesus say this? Because he knows life is full of what economists call “opportunity cost,” that saying “yes” to one thing means saying “no” to other things.

The point is that we were made for God and not for the earth or for ourselves. Because of this we must learn to discipline our animal desires (or any desire, for that matter). This means first learning to say no to things. And saying no to something is not the same as the resignation that comes when a thing is all gone. Saying no is actually quite straight forward: a thing is there, you can have it, but you choose not to for a reason. That “reason” is critical, which Milton says when lost is like a city who has lost its king. If we have never built up the muscles of self-denial or tightened the sinews of temperance, then how can we expect to resist the tempter? If we have never formed habits where we say no to any desire that might wish to be gratified, then the likelihood that we will resist temptation when it comes is very, very low.

This is why it’s important to consider the Lenten season as a training program of the Christian virtue of self-denial. If this sounds ascetic or out of bounds for a classical school to bring up, recall what C.S. Lewis says, that education is about how “the head rules the belly through the chest.” How can the belly be ruled if we are so used to gratifying its desires? How can we resist temptation without some applied skill in this? The virtue of denying self and putting God (and others) first is critical. Man does not live by bread alone. Think of it another way.

Self-denial can be justly regarded as temperance, that virtue which the historic Church has said “ensures the will’s mastery over instincts and keeps desires within the limits of what is honorable.” This talk of temperance can be confusing, however. On the one hand, many American Christians are well-acquainted with “temperance” and its historic vestiges. (Local craft beer is only just coming back from what it once was since the 21st Amendment.) On the other hand, of the four cardinal virtues there is perhaps no more unpopular virtue for American Christians than that of temperance. Perhaps it is because the practice of temperance might include fasting, and the very idea of denying oneself a bodily good smacks of works righteousness. Perhaps it is because the practice of temperance wars against the consumerism in our bones. Perhaps it is because it’s just not in human nature to easily or voluntarily give up innocent pleasures to which one has grown accustomed.

Regardless, observing Lent and strengthening the muscles of temperance was never meant to be reduced only to fasting. Traditionally, Lent included three disciplines: prayer, fasting, and alms-giving. And today these couldn’t be timelier. It would be no bad thing for students, parents, teachers, administrators to have such practicable piety attending all our efforts during this quarantine. The heralds of “shelter in place” are loud. But they shouldn’t drown out the historic voice of the church which calls us to participate in the Lenten season. For Lent reminds us that there is always a deeper “shelter in place” for the soul to abide amid the desiderata of the age.

By this we might find true contentment. That is the paradox of self-denial, that it makes room in the end for greater joy. Hopkins puts it best: “Palate, the hutch of tasty lust, Desire not to be rinsed with wine: The can must be so sweet, the crust / So fresh that come in fasts divine!”

Devin O'Donnell

Devin O’Donnell is the author of THE AGE OF MARTHA. He has taught and worked in classical learning for over 15 years. In 2009, he and some crazy families founded a classical Christian school in California, where he later served as headmaster. In 2015, he was Research Editor of Bibliotheca. Currently, he is the Director of Family & Community Education at The Oaks Classical Christian Academy. He also teaches Great Books and is a classical hack, who came up through the manhole covers of learned society to find wisdom.