How Beowulf Can Help Us Understand the Atonement

Dating to sometime between the 8th and 11th centuries, Beowulf is the oldest surviving old English long poem. It corresponds to a period in English history where Anglo-Danish people made up a large portion of the British Isles’—a multiethnic makeup which is reflected in the story itself—and its style and theme are planted in the Germanic heroic tradition. However, and despite its use of some Norse pagan symbolism, it has some explicitly Christian components. The scholarly consensus is that the Christians aspects were added at a later date by an unknown redactor; however, even if that’s true, the typology in Beowulf offers profound theological insights.

Oftentimes, those of us raised in the modern Church are unaware of the robust theological views of our forbearers. I, myself, didn’t discover so influential a work as Athansius’ On the Incarnation until after my first year of undergraduate work (and even then, it was an accidental discovery at a used bookstore). One area largely abandoned post-Reformation has been the Early Church’s teaching on the theology of the Atonement.

If you go into the average, orthodox Evangelical Church on a given Sunday and ask the question, “What did Jesus accomplish by dying on the cross?” the answer would look something like this: humanity’s fall placed us under the wrath of God so Christ saved us from that wrath by paying our penalty through his death.

Much about this view is to be commended. There are certainly verses which support the main thrust of the argument. However, it’s incomplete. The teaching of the Early Church is that Christ’s death on the cross was a multi-faceted event. Humanity’s sin brought God’s wrath because in it, we chose the dominion of Satan and rebellion against God. God sent Christ on a rescue mission to destroy the devil and rescue his captives. This view is summarized in Hebrews 2:14-17:

Since the children have flesh and blood, he too shared in their humanity so that by his death he might break the power of him who holds the power of death—that is, the devil—and free those who all their lives were held in slavery by their fear of death. For surely, it is not the angels he helps, but Abraham’s descendants. For this reason he had to be made like them, fully human in every way, in order that he might become a merciful and faithful high priest in service to God, and that he might make atonement for the sins of the people.

St. Irenaeus (130-202 CE) fleshes out this perspective: “Adam had become the devil’s possession, and the devil held him under his power. Wherefore he who had taken man captive was himself taken captive by God, and man who had been taken captive was set free from the bondage of condemnation.”

The ultimate pattern of Truth is Christ crucified on the cross. While pagan cultures have an insufficient understanding of this, their tales and stories can unknowingly reflect this transcendent pattern of Truth.

Interestingly, Beowulf can be a teaching tool to convey this rich, holistic theology of Atonement.

Throughout the story, the protagonist Beowulf is often connected to Christ in some way. The first mention of him shows he was sent into the world by the divine: “God sent him for a comfort to the people. He had marked the misery of that earlier time when they suffered long space, lacking a leader. Wherefore the Lord of life, the Ruler of glory gave him honour in the world.” One can find Scriptural parallels in Isaiah 9:6, 2 Corinthians 1:3-5, and 2 Thessalonians 2:16 where Christ is shown to be sent by God as a comforter.

What’s more, Hrothgar praises Beowulf’s mother, saying, “Lo! A woman who has borne such a son among the peoples, if she yet lives, may say that the ancient Lord was gracious to her in the birth of her son.” (emphasis mine). In Scripture, Mary is said to be “full of grace” (or “highly favored;” see Lk. 1:28). The Catholic prayer, “Hail Mary full of grace, the Lord is with thee. Blessed art thou among women and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus Christ. Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death” echoes similar themes. Interestingly, St. Justin the Martyr (100-165 CE) talks about Mary in conjunction with the Atonement, “by means of her [Mary] was he born, concerning whom we have shown so many Scriptures were spoken; through whom God overthrows the serpent, and those angels and men who have become like to it, and on the other hand, works deliverance from death for such as repent of their evil doings and believe in him.”

Throughout the story, Grendel and the other foes fought by Beowulf are types of Satan. Grendel dominates the hall, taking the life out of it, literally and symbolically. He’s associated with Cain on multiple occasions and behaves like a demonic berserker. He is even said to have borne God’s anger.

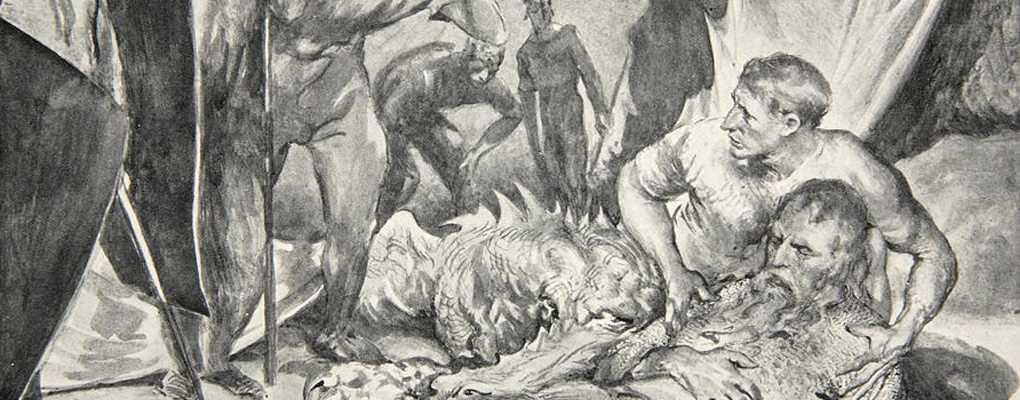

During the battle between Beowulf and Grendel, Beowulf mortally wounds the monster, which echoes of the protoevangelion (which means “the first pronouncement of good news”) in Genesis 3:15. Beowulf also has to descend into a cave to battle Grendel’s mother, which can parallel Christ descending to the dead, something acknowledged in the Apostle’s Creed. His third and final battle is against a dragon (a symbol used frequently for Satan in Early Christianity). In this battle, Beowulf dies, but he is successful at delivering the people from the dragon, much like Christ’s victory came in his death.

It’s probable that most of these connections were not made intentionally by the original authors and would have been lost on the original audience. Nevertheless, they can powerfully present the Gospel. All truth flows from God. The ultimate pattern of Truth is Christ crucified on the cross. While pagan cultures have an insufficient understanding of this, their tales and stories can unknowingly reflect this transcendent pattern of Truth. After all, “the Devil has no stories.”

Though the explicit Christian components may have been the work of the story’s later redactors, the pattern of the story still mirrors that of Christ’s. Even where there are inconsistencies between Beowulf and the pattern of Truth, Christians can exploit them to communicate the truths of the Gospel. For instance, Beowulf may be a victorious, Christ-like figure but he ultimately dies fighting the dragon. While Beowulf is “immortal” in the sense that he lives on through story, the Christian God makes a fool of death (cf. 1 Cor 15:55) because the grave cannot keep him dead. The resurrection is the vindication of Christ’s ultimate victory.

All stories stem from the patterns and rhythms of salvation-history. Beowulf, as a fierce warrior and liberator, is able to act as a type of Christ. By studying this symbolism, Christians can sharpen their own theology and develop a more holistic view of the Atonement.