Classical Education and the Cultivation of the Christian Imagination: Part 2 – Late Antiquity and the Truly Christian Education

In part one of this two part series, Mr. Betts described the purpose of the truly Christian classical education, then considered the ways that a classical educations which left out Christianity ultimately failed famous philosopher and pedagog, John Stuart Mill. This is part two.

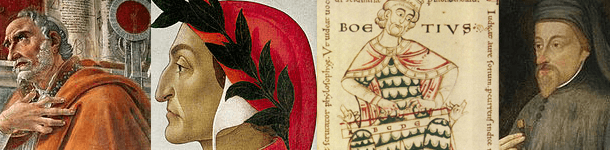

To avoid this result for our students, classical educators, in my opinion, must pay attention to the period of Late Antiquity. In the period of 350-550 AD, the Classical world became Christian. At the conversion of Constantine, the world of antiquity was largely pagan, but by the end of Justinian’s reign, it was thoroughly Christian. During that period a variety of Christian thinkers engaged the classical world, integrating the Biblical and the Classical perspectives. Their works, when included in an educational program, can remedy the separation of the Classical and the Christian that Mill experienced.

As a candidate period for study, Late Antiquity is not perfect. As a matter of Latin style, the authors of that period are inferior to Cicero, Virgil, and the early period of the empire. Macrobius and Cassiodorus, two sixth century authors of enormous influence in the Middle Ages, are excessively wordy and not suitable for the beginning Latinist. Likewise, the philosophy of Late Antiquity may be deficient. Neo-Platonism is the prevailing philosophical strain at this time amongst both Christian and Pagan writers. Aristotle, to the extent that he is understood, is comprehended in Neo-Platonic terms.

Nonetheless, the richness of the discourse is worth the study. This period was co-incident with the Fall of Rome. As a consequence, there was a great deal of weighing the past and preserving it as the threat of barbarism grew closer. Handbooks for the study and propagation of the Liberal Arts were produced by many authors for this purpose.

The obvious giant of Late Antiquity, particularly for those of us in the Latin West, was St. Augustine. His influence over theology, philosophy, ecclesiology, and education is immense. The Confessions, The City of God, and On Christian Doctrine are relevant for study by classical students. Apart from the early books of The Confessions, those that are biographical rather than philosophic, the study of Augustine probably should be reserved for a post-secondary context.

Boethius (480-525 AD) is a good candidate for study by our students as a representative of this period. The adopted son of a Christian Roman Senator, he entered a life of intellectual pursuit as well as service to the crumbling empire, at that time under the control of the Gothic and Arian king, Theodoric. Boethius produced a variety of works on Mathematics, Logic, and Music. These works were profoundly influential through the 13th century. His theological treatise, On the Trinity, attempts to comprehend the trinity in strictly rational and metaphysical terms, remaining a text to be reckoned with through the time of Aquinas.

The Consolation of Philosophy, a short treatise by Boethius, written while he awaited execution by Theodoric, is a masterpiece, accessible to students, with poetic and philosophical excellence. The work begins as a lament for false imprisonment and the vagaries of fortune. In the text, Boethius is consoled by the figure of Lady Philosophy. She gently guides him to understand his predicament from a more philosophical perspective. The book is a compilation of prose sections alternating with poetry. The central poem “O qui perpetua” is one of striking beauty and insight. It closes with this passage:

“Grant, Oh Father, that my mind may rise to Thy sacred throne. Let it see the fountain of good; let it find light, so that the clear light of my soul may fix itself in Thee. Burn off the fogs and clouds of earth and shine through in Thy splendor. For Thou art the serenity, the tranquil peace of virtuous men. The sight of Thee is the beginning and end; one guide, leader, path and goal.”

Lady Philosophy cures Boethius of his despair through philosophical inquiry. The final section explores the nature of God’s providence in a world of chance and fortune. The error of thinking of God as a being in time as opposed to one over time is explored. God is an eternal being rather than a perpetual being. This alters how Boethius thinks of providence and divine causation.

The Consolation represents a work to be studied both for its intrinsic merits and for its influence on subsequent culture through many writers, political figures, and artists. Its influence began to wane only with the coming of Descartes, Francis Bacon, and the Scientific Revolution. Both Bacon and Descartes encouraged the West to turn away from prior classical Philosophy, and especially Metaphysics. They sought to improve our material lot by focusing on the material. Consequently, by the 1700’s, The Consolation, with its philosophical emphasis, lost much of its power as a formational work in the Western Mind.

The Consolation represents a work to be studied both for its intrinsic merits and for its influence on subsequent culture through many writers, political figures, and artists. Its influence began to wane only with the coming of Descartes, Francis Bacon, and the Scientific Revolution. Both Bacon and Descartes encouraged the West to turn away from prior classical Philosophy, and especially Metaphysics. They sought to improve our material lot by focusing on the material. Consequently, by the 1700’s, The Consolation, with its philosophical emphasis, lost much of its power as a formational work in the Western Mind.

Prior to that, the effect of The Consolation on culture was large. Alfred the Great (849-899 AD), in the peace that followed after defeating the invading pagan Danish army, sought to re-establish learning amongst the clergy and the laity. He established schools modeled after Charlemagne’s. Alfred personally participated in the translation of The Consolation for his own edification and for the education of his children.

Political life is always subject to the vagaries of fortune. The special gift of The Consolation is to calm the souls of those bemoaning their political fate. The work appeals especially to monarchs and temporal leaders. In the sixteenth century, Queen Elizabeth I watched closely the progress of the Protestant Reformation in continental Europe. A great blow to the Reformation in southern Europe occurred when Henry of Navarre in Spain converted back to Catholicism before ascending to the throne in France. Elizabeth, an accomplished Latinist, was discouraged by this development. To lift herself and her spirits, she translated, by her own hand, The Consolation into English.

The effect of The Consolation on literature is large, as well. Two prominent authors among those influenced were Dante Alighieri and Geoffrey Chaucer. Even though Boethius lived seven centuries before them, the central place that he played in their imaginations is great

Prior to writing the Divine Comedy, Dante had a relationship of courtly love with a young woman named Beatrice Portinari. When Beatrice died, Dante was despondent and sought comfort in The Consolation, a book with which he personally had not been familiar prior to that time. He found it to be very helpful, such that when he wrote the Divine Comedy much of the role of the Beatrice character was informed by The Consolation. Beatrice serves as a guide of Dante through The Purgatorio and also in The Paradisio. She exhorts him to greater understanding, much in the manner of Lady Philosophy in The Consolation. Dante includes Boethius in The Paradisio, praising him as a “sainted soul.”

The influence of Boethius and The Consolation on Geoffrey Chaucer is even more direct. Chaucer was a man of politics, working as a diplomat, and of great Christian faith. He translated The Consolation in full. There are numerous references to Boethius and The Consolation in his many works. The Knight’s Tale in The Canterbury Tales shows this clearly, as he reflects on the lovers’ misfortunes with Boethian wisdom. The women of that story are also prominent in dispensing wisdom which cools the passions of the men, in a manner akin to Lady Philosophy.

At the end of The Canterbury Tales, Chaucer comments on many of his works that he regrets for one reason or another. Regarding Boethius, though, he is unequivocal:

“But for the translation of Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy and other books of saints’ legends, homilies, moralities, and devotions, I thank our Lord Jesus Christ and his blessed Mother, and all the saints of heaven, beseeching them that they from henceforth unto my life’s end send me grace to lament my sins, and to meditate upon the salvation of my soul, and grant me the grace of true contrition, confession, and satisfaction for sins in this present life…”

Whether educators choose a work like The Consolation or another from the Western tradition, attention must be given to presenting the classics in harmony with Christian development. Reflection on the authors of Late Antiquity in a Classical education can accomplish this. Such attention will more properly guide the moral imagination of our students and give them a more unified picture of what Western Culture is.

Romano Guardini, writing in the early 1950’s in his book, The End of the Modern World, speaks to those classicists such as Mill, as well as more formidable ones like Nietzsche, who seek to divorce the Classics from Christianity. He notes:

“In many cases, the non-Christian today cherishes the opinion that he can erase Christianity by seeking a new religious path, by returning to classical antiquity from which he can make a new departure.”

Those, like Mill, who seek this path, are mistaken about antiquity. Classical education following the time of Christ is of necessity Christian. As Guardini asserts:

“As a form of historical existence classical antiquity is forever gone. … Even at the height of their cultural achievement the religious attitudes of the ancients were ancient and naive. Classical man lived before that crisis which was the coming of Christ. With the advent of Christ, man confronted a decision which placed him on a new level of existence…. With the coming of Christ, man’s existence took on an earnestness which classical antiquity never knew simply because it had no way of knowing it. The earnestness did not spring from a human maturity; it sprang from the call which each person received from God through Christ.( p. 101-2)

We can all say a hearty “Amen” to this and bear it in mind as we craft our classical educational programs.

Bibliography

Mill, John Stuart. Autobiography.Penguin Books, London, 1989.

Guardini, Romano. The End of the Modern World. ISI books, Wilmington, DE, 1998.

Kirk, Russell. “The Moral Imagination.” in Literature and Belief Vol. 1 (1981), 37–49

Further Reading

Patch, Howard Rollin. The Tradition of Boethius: A Study of His Importance in Medieval Culture. Oxford University Press, New York, 1935.

Chadwick, Henry. Boethius: The Consolations of Music, Logic, Theology, and Philosophy, Claredon Press, Oxford, 1981.

The Cambridge Companion to Boethius. Marenbom, John (ed.), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2009

Pelikan, Jaroslav. The Excellent Empire: The Fall of Rome and The Triumph of The Church, Harper & Row, San Francisco, 1987.

Pelikan, Jaroslav. Eternal Feminines: Three Theological Allegories in Dante’s Paradisio, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ, 1990.

Ross Betts

Ross Betts is the president of the American Friends of http://www.augustinecollege.org/">Augustine College.

He is a practicing nephrologist in Butler and Armstrong Counties in Western Pennsylvania. He graduated from Vanderbilt University, 1980, Summa Cum Laude, in Chemistry and from the University of Michigan Medical School in 1984. His subsequent training was in Internal Medicine at the University of Minnesota and at Washington University in St Louis in Nephrology.

Ross has served on the volunteer faculty at the University of Pittsburgh and taught residents at Mercy Hospital in Pittsburgh, presently teaching a class on “Humanities and Medicine” there. He serves on numerous hospital boards and in administrative positions. He is on the Academic Committee of Aquinas Academy in Pittsburgh. He is the science editor of Classical Education Quarterly (CEQ), a publication of the Consortium for Classical Lutheran Educators. He writes articles for CEQ and has written numerous articles for Living Magazine, a publication of Lutherans for Life. He is married to Lynn and has five children. They attend Bethel Lutheran Church(LCMS) in Glenshaw, PA.