Subverting Narnia

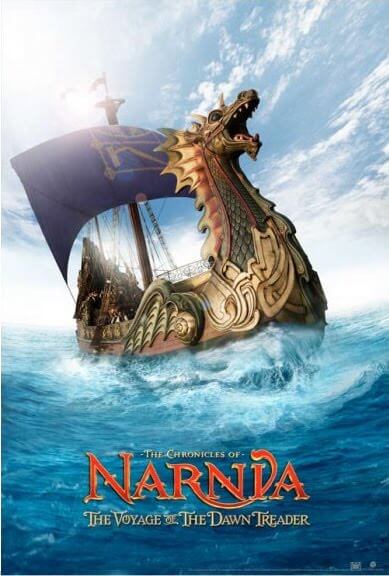

On December 10th, Walden Media and 20th Century Fox will release The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, their third attempt at bringing to life C.S. Lewis’s classic series of books.

On December 10th, Walden Media and 20th Century Fox will release The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, their third attempt at bringing to life C.S. Lewis’s classic series of books.

When Walden announced they had secured the rights to the books in 2001 many of the series’ fans were ecstatic, hopeful that these beloved stories would be given the same loving treatment that Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings books were granted. However, it quickly became clear that the producers of these films were less in love with the Narnia stories than was Peter Jackson with the tales of Middle Earth. Jackson was obsessed with the mythology of the LOTR books and his dedication to making Tolkien’s world and themes come to life shone through in his films in such a way that what changes he made to the plot didn’t substantially alter the effects the story renders. Much of what made the books meaningful made the films meaningful as well.

Not so in the Narnia films.

In fact, as Steven D. Boyer argues in the current issue of Touchstone Magazine, the films are “very far from a faithful representation” of Lewis’s original stories. Boyer, a professor at Eastern University, claims that, whereas the Narnia books employ medieval archetypes to present “deeply Christian imaginative themes”, the Narnia films all but ignore those important themes and instead offer a downright disappointing pastiche of Hollywood modernism. A series of books that present readers – young and old alike – with honorable, sacrificial characters; meaningful relationships and hierarchies; and a reminder that the world can be a “beautiful, elegant, adventurous, festive place” somehow has become a series of movies that instead propagate individuality above “submission to rightful authority”; youthful indiscretions as simply “emotional realism”; and power as “the ability to make others do what you want.” Mr. Lewis would appalled.

Boyer makes clear that his primary concern is not with whether the books translate well to the screen – that is, whether they are naturally cinematic – or whether the movies are good from a filmic standpoint. Rather, he sets out to answer the questions “do the films ‘do’ what Lewis’s books themselves ‘do’?” And “do those who see the films come away nourished in the same way that readers of the stories do?” “Do the films,” he asks, “give us something recognizably like Lewis’s comprehensively Christian vision of the world?”

Doubtful, he concludes, on all three counts.

Mr. Boyer argues that the films fail to fully capture the comprehensively Christian worldview by which Lewis saw the world and through which he conceived his stories primarily by ignoring Lewis’s dedication and belief in rightly ordered hierarchy. They do this, Boyer argues, in three ways: by pushing Aslan to the “periphery” of the tales, by recasting High King Peter as an immature weakling, and by portraying the relationship between Peter and Prince Caspian as one of “almost unrelieved hostility, suspicion, and animosity.”

To Lewis, Boyer insists, the affirmation of rightly ordered hierarchy is central to truly Christian thought. He writes:

“Lewis’s thinking begins with the Christian understanding of God as the creator of the world, and of the world as God’s creation. The historic Christian doctrine of Creation…insists upon hierarchy… it is clear that any serious doctrine of creatio ex nihilo involves the recognition of a very real hierarchical distinction between Go and world…the one is utterly independent, the other utterly dependant.”

Boyer goes on to argue that in conjunction with this “affirmation of hierarchy” is the “insistence that creation is.. unambiguously good.. with a goodness that grows directly out of its unqualified dependence upon its Creator.” But as soon as that creation refuses to submit to its Creator it “ceases also to be good” and instead enters into competition with the Creator. Such was the case with Satan. To Lewis, Boyer suggests, this “is the essence of sin: it is a turning away from our true creaturely status.”

So hierarchy, contrary to most modern thought, is fundamentally good and an essential part of Christian life and thought.

But what does this have to do with Narnia? Well, according to Steven Boyer, everything.

Consider:

“Narnia is a great repository of hierarchical images and relations – of good kings and noble knights, of laborers who are not disgruntled and servants who are not demeaned, of Aslan the great Lion who rules over all, who is never safe, but always good.

One can hardly turn a page of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe or of Prince Caspian without encountering compelling images of royal authority and knightly virtue – and we see now that both of these themes are intimately connected with Lewis’s positive construal hierarchy, which in turn if foundational to his distinctively Christian vision of reality.”

Yet in the film adaptations of these stories we see none of this. Sure, we see knights, kings, queens, duels, battles, even a little bit of sacrifice. But we don’t see the meaning behind such motifs. We don’t see true chivalry. We don’t see the importance of honor. We don’t see rightfully ordered relationships. And, perhaps most disturbing of all, we don’t see Aslan as the center of the story.

The Narnia books are not chiefly about Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy, as evidenced, in part, by the fact that they are in only a few volumes. The Chronicles of Narnia are about, above all, Aslan and his work in this magical, mysterious world, about his work in the lives of Narnians and how he uses boys and girls from “our world” in this work. But the films instead turn the tables and Aslan becomes little more than a helpful secondary character, much like the butler, Alfred, in the Batman tales. Sure he is wise, kind, and generous in his own ambiguous way, but he is interesting mostly because he is a talking lion and less due to the quality of his character. In fact, Walden Media’s Aslan is far less interesting and meaningful a character than Harry Potter’s Albus Dumbledore. One doesn’t come away from the film in awe of Aslan like one does from the books, nor is it palpable why he is spoken of as “ not safe… but good.”

So if the story isn’t centered upon Aslan then where is its focus? In the case of the films: Peter. This in itself is remarkable when one considers the theological implications of such a change, but beside that troubling thought the Peter we meet in the films is not the same young man Lewis introduces in the books.

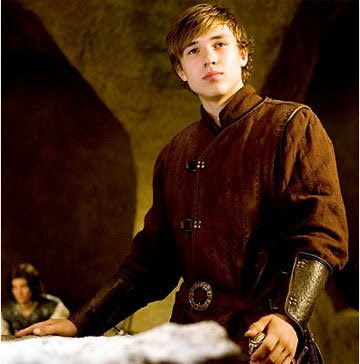

On the contrary, the Peter of the films is insufferably arrogant, condescending, and power hungry.

Consider this striking list of scenarios Boyer provides:

– In Prince Caspian “we first encounter Peter as the cause of a brawl in a London subway, which he started simply because someone bumped him.”

– “Once in Narnia, Peter sets out to lead the other children and gets hopelessly lost, but he keeps insisting… ‘I’m not lost…”

– “When he finally assumes command of the Narnians and then is confronted by Lucy, who tries to sense into him and get him to wait patiently for Aslan, he condescendingly replies, ‘I think it’s up to us now… We’ve waited for Aslan long enough.’”

– “In the enemy castle, in the midst of their failed attack, Peter stupidly and obstinately refuses to call for retreat, crying out instead, ‘No, I can still do this!’ – which prompts Susan to ask, ‘Exactly who are you doing this for, Peter.’ ”

In response to these examples, and others like them, Boyer comically refers to this version of King Peter as a “young, handsome version of Homer Simpson.” This Peter doesn’t respect authority, has no sense of his place in the hierarchy at the top of which sits Aslan, and has a thoroughly immature understanding of what honor is. It would come as no surprise if we discover in the next film that he has a special liking for donuts and Duff Beer. As Boyer aptly puts it, “his folly is the driving force behind most of the action in the movie.”

In response to these examples, and others like them, Boyer comically refers to this version of King Peter as a “young, handsome version of Homer Simpson.” This Peter doesn’t respect authority, has no sense of his place in the hierarchy at the top of which sits Aslan, and has a thoroughly immature understanding of what honor is. It would come as no surprise if we discover in the next film that he has a special liking for donuts and Duff Beer. As Boyer aptly puts it, “his folly is the driving force behind most of the action in the movie.”

Take for example the film’s depiction of Peter’s relationship with Prince Caspian. To Adamson and co., Caspian and Peter are rivals, unable to cooperate or share power. Their understanding of power is downright Miraz-ian. In fact, Boyer reminds us, it is evil King Miraz who says that he doesn’t believe in the Pevensie legend because it would be impossible for there to “be two Kings at the same time.” And it appears, Walden Media agrees with him.

Unfortunately Peter’s primary interactions with Caspian are childish conflicts built upon his need to blame someone:

“When Lucy asks what happened in the battle, Peter spitefully replies, “Ask him.” Caspian is shocked to be blamed, and he retorts, “You could have called it off. There was still time.”

Peter: “No, there wasn’t, thanks to you. If you had kept to the plan, those solders might be alive right now.”

Caspian: “And if you had just stayed here like I suggested, they definitely would be!”

Peter: “You called us, remember?”

Caspian: “My first mistake.”

Peter: “No, your first mistake was thinking you could lead these people.”

Compare that interaction with this one, from the book:

“In Lewis’s story, that meeting takes place just after Peter has leaped in to help Caspian in a fight with the deceitful Black Dwarf Nikabrik. As the heroes catch their breath after this deadly clash, the following remarkable exchange occurs:

“We don’t seem to have any enemies left,” said Peter. “There’s the Hag, dead. . . . And Nikabrik, dead too. . . . And you, I suppose, are King Caspian?”

“Yes,” said the other boy. “But I’ve no idea who you are.”

“It’s the High King, King Peter,” said Trumpkin.

“Your majesty is welcome,” said Caspian.

“And so is your majesty,” said Peter. “I haven’t come to take your place, you know, but to put you into it.”

As Boyer puts it, we’re in a different world here. “ There is no pompous ego or arrogant competition here. Instead, we find nobility, authority, courtesy, and humility all wrapped into one.”

But why did the producers of the films feel the need to distort Lewis’s depiction of Peter like this? Well, according to director Adamson, it is because it would be a “really hard” thing for a kid who was once a king once to give it up and go on with his normal life. As Boyer puts it, Adamson hoped this “emotional realism” would “create depth for the characters” because, after all, most of us would react negatively if placed in a similar situation. That is true, Boyer says, but “that is because we have not breathed the air of Narnia.”

“We are thinking like ordinary persons (and worse, like self-sufficient, twenty-first-century, Western intellectuals) instead of like knights of kings. In Lewis’s telling of all of the Narnia tales, the children’s experiences as kings and queens…consistently transform them into nobler, more virtuous people in their own world. They are not spoiled people in their own world. They are noble kings who carry that very nobility back into their non-royal roles as schoolchildren.”

It is this very nobility of character that sets Edmund and Lucy apart from their snivelling little cousin, that “record-stinker” Eustace Clarence Scrubb, a boy “who almost deserved” his hilariously awful name.

Indeed, as the Pevensie children grow and change for the better through their Narnian experiences, so should the children who read them. Each child who dives into a Narnian adventure should come away with an ability to recognize honor, chivalry, courage, nobility, sacrifice, and much more. But do the children who have watched the first two films come away with this ability? We can only hope that behind the mess Walden Media has made a ray of light shines through, that somewhere wisdom and virtue will be recognizable. Of course, it is up to us to help them see it.

Just something to think about before you spend your Christmas vacation in front of a multiplex big-screen. And, as always, we recommend you read the book first.