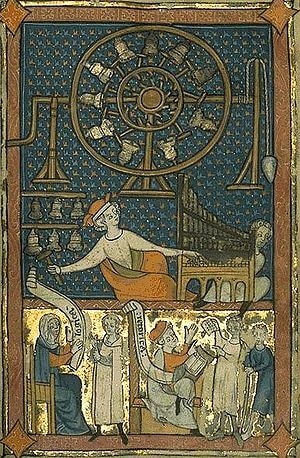

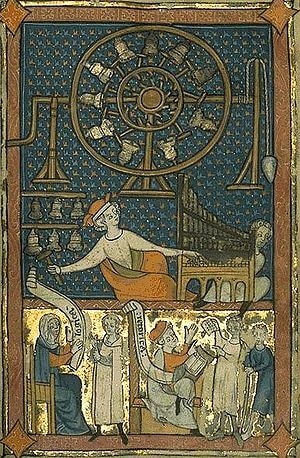

The Capstone of the Trivium

- Image via Wikipedia

In my previous post I argued that the Christian classical tradition believes in knowable truth, and therefore it cultivates the tools that enable us to know the truth. On the other hand, conventional education does not believe in knowable truth, so it does not waste its time cultivating tools for something it does not believe in.

Their love for truth led our ancestors to cultivate the seven liberal arts: the three verbal arts of grammar, logic, and rhetoric so that we could use language to discover and communicate truth about the world around us and about the working of our own souls; and the four mathematical or rational arts of arithmetic, geometry, music (harmonics) and astronomy so that we could know the nature of the world outside our minds.

I don’t want you to get lost in wondering why music and astronomy are mathematical arts or even what I meant by “rational arts,” so I’ll make this conditional promise that I will try to develop those ideas in a later post. In the meantime, I promised at the end of my last post to develop the idea that rhetoric is the capstone of the liberal arts and that we can apply our insights from thinking about rhetoric to the pursuit of wisdom through writing. So let me address those matters directly.

What does it mean to say that rhetoric is the “capstone” of the verbal arts? I’m using the term in its metaphorical sense as a “crowning achievement” or a “culmination.” Mastery of rhetoric depends on the prior mastery of grammar and logic. We need to remember this fact, because we have a tendency to teach classes as subjects and to regard them all as of equal value.

The liberal arts are different. They make up the trunk of the tree of wisdom because everything else that can be learned, every branch of knowledge, depends on them. The highest liberal art, rhetoric, depends in turn on the lower arts of grammar and logic.

This implies a natural hierarchy of learning that many modern educators are not comfortable with. Unfortunately, if you dismiss this hierarchy, you have severed the branches from the trunk, robbing them of their sustenance.

Rhetoric plays a crucial role in that it completes the trivium and it bridges the scholar’s path to every subsequent subject.

Rhetoric completes the trivium by combining all that was learned in grammar and logic into one activity and then applying what was learned to a specific function. What that specific function is provides us with our definition of rhetoric.

Unfortunately, different people have given us different definitions. Aristotle called rhetoric the art of persuasion. Some people see it as the art of manipulating an audience. I’ve called it the art of the fitting expression. But I think that the most accurate description of what happens during a rhetorical encounter is expressed by Plato in his dialogue The Phaedrus. He called it “The art of leading the soul with words.”

Plato argued that rhetoric, because of what it was, needed to be subordinated to what he called dialectic, which was the pursuit of the truth.

A brief, technical digression (feel free to skip to the next paragraph): Sometimes dialectic is used to refer to logic, but I think for this context we need to note a distinction. Dialectic in Plato is really another word for philosophy more than a reference to a technical art of reasoning. Logic as we think of it today is an art developed and refined by Aristotle and found in classical schools and the occasional college. It’s a crucial skill or art for the philosopher (not the academic specialist but the true lover of wisdom) to develop, and therefore it’s a crucial skill or art to teach in a classical school. But it isn’t the same thing as the fully orbed dialectic that Plato refers to in his dialogues.

The simplest way to clarify this point is probably through this simple assertion: to Plato the pursuit of truth is more important than the ability to persuade. Once you can perceive the truth, then you should try to persuade others to see it too, but until you do, you may be better off not learning the tools of rhetoric.

Should we stop teaching rhetoric, then? I don’t believe we should, but when we teach students rhetoric, we must be doing so in a context of truth seeking. In fact, we must use rhetoric to give our students practice seeking truth.

When we do, we cultivate wisdom in our scholars. Now, I should clarify two points. First, there are no guarantees. Teaching rhetoric in and of itself does not make one wise. However, I am going to contend that apart from rhetoric (the real thing, not the class), our pursuit of wisdom will be continually hindered by our lack of discipline.

Second, writing is a subset of rhetoric. Therefore, much of what we can do with rhetoric will apply to writing. After all, writing is also an attempt to persuade or to manipulate an audience or to lead the soul through words.

So moving forward, I will focus on how writing can help us in our pursuit of wisdom. And my first point about writing will be my last point in this post: by teaching writing correctly, that is, as rhetoric – the third art of the trivium, the culmination of the trivium – we bring grammar and logic to their fullness, not in technical rules or mind-bending games, but in the honorable pursuit of truth and the subsequent ability to move the souls of others to the truth gained.

In my next post on this topic (12/1) I will explore more specifically and practically just how it is that the art of rhetoric/writing enables us to seek the truth and to lead others to it. See you then!

If you have read this far, you will probably be interested to know about an opportunity to explore this topic in a live workshop with Leah Lutz (in California) or with me (in North Carolina). On December 4, Wisdom Through Writing day, each of us will be presenting a one day workshop on How To Cultivate Wisdom Through Writing. Seats remain, so please don’t hesitate to sign up HERE or click HERE to learn more, including the tentative program. If you have any trouble on-line, PLEASE call us at 704 786-9684.

Related articles

- Classical Rhetoric 101: An Introduction (artofmanliness.com)

- Aristotle’s Practical Philosophy on Ethics and Politics (epages.wordpress.com)

- The Library of Rhetoric – A Network for the Study of Effective Communication (libraryofrhetoric.org)